Assessing tough sustainability decisions: Informing expert intuition

Photo courtesy NASA

More advanced techniques

Mathematical discounting only attempts to reflect human behaviour—how we, collectively and as individuals, deal with time and uncertainty. The reality is the human behaviour; the mathematics seeks to model it, so we can better assess alternative courses of action.

More importantly, any complete sustainability analysis has to allow for the possible presence of what are termed “real options.” This concept was developed in management research in the 1980s, and has become an increasingly important element in making business decisions. While quantified real options analysis can be a complex process, being able to understand the concept can be valuable to the decision-maker. The holder of a real option, typically a present or future decision-maker, has the right, but not the obligation, to take some action, perhaps expanding, abandoning, or changing the use of a building. Some real options may run with a project without being exercised for decades, and may be used, when deemed appropriate, by some future decision-maker. In some of this author’s work in real options, the Prince Edward Viaduct over the Don Valley in Toronto is used as an example. Completed in 1918, it incorporated provisions for a subway line, something not installed for 50 years. The decision-makers, before World War One, consciously paid to create this option. When we design resilience and flexibility into buildings we are doing much the same thing—making provision for things that might, or might not, happen. Interestingly, within an options framework, the value of that option did not depend upon whether it was actually used or not. The original decision-makers for the viaduct could not have been expected to predict the wars and economic turmoil that would occur over the next few decades. Real options in buildings frequently occur naturally; the challenge to the designer or property manager is in identifying them.

A commonly encountered real option is the possibility of waiting, deferring some action knowing it can be done in the future. Conceptually this is retaining the option to undertake the action. Mathematically, such an option may be worth more than the present value of exercising it immediately, especially when there is considerable uncertainty present. Waiting may provide additional information, the market situation may change, or new technologies may emerge.

While finance and management books present mathematical formulae to deal with uncertainty and to calculate option values, another route is to undertake Monte Carlo analysis. This involves the simulation of the decision alternatives and possible outcomes over time. Significant risk factors are incorporated in the model as estimated probability distributions, and the model is run multiple times, often thousands of times. This generates expected values, distributions, and confidence limits, which reflect the diversity of outcomes that may occur.

Building a simulation model using a spreadsheet program has the advantage of forcing the model-builder (hopefully, also the decision-maker) to identify and assess the nature of the situation over time, relevant risks, and risk distributions. It is possible, depending on the amount of time put into developing the analysis, to consider possible management responses to future events, in particular whether available real options might be exercised.

Interpreting the results

Relative to sustainability, in the construction world, no realistic method will give a clear single answer: there are just too many uncertain variables, and data quality is low. Every building is unique—even franchise fast-food restaurants are built on different sites. It is different in the financial area, where assets, such as stocks and bonds, are uniform, and minute-by-minute data may be available going back decades. For the construction decision-maker, poor and uncertain data means the outputs from any decision method will need interpretation.

Given the usual amount of uncertainty surrounding input data, sensitivity testing can be very revealing. This is the organized (or hopefully somewhat organized) varying of data inputs to explore the results. For example, one might make a base assumption about the life of a building or building component, but vary it to see how making it longer or shorter might change the preferred alternative.

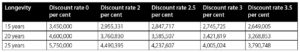

Returning to our earlier example of a choice between two pieces of equipment, to perform sensitivity testing, one might perform the calculations using various discount rates, and for various longevity values (Figure 2).

One issue with sustainability decisions is the presence of multiple measures: often the decision-maker has to consider energy consumption, CO2 emissions, initial costs, and operating costs. When dealing with these, sensitivity testing around equivalences can offer a further level of insight.

Monetary measures can be used to connect different measures within the context of the decision-maker’s priorities relative to sustainability. Scheme A might involve trading off some building feature to achieve a building with lower ongoing CO2 emissions. How much is being initially paid for this ongoing saving? Does it make sense? How does it compare with market values for CO2 emissions? One might make some assumptions about the situation regarding the relative value of future CO2 emissions, and test those assumptions to see how the results might vary.

The findings resulting from sensitivity analysis can sometimes be interpreted using the following logic. One outcome possibility (a) is the answer is fairly clear: Alternative A is preferred over Alternative B under any realistic data assumptions. Another outcome (b) is any difference in results is marginal. In this case, the data uncertainties and assumptions will prevent identification of one clear “best” answer and the decision-maker might choose on the basis of intuition. In between these two extremes is an area (c) in which one alternative is usually favoured, but not always. This warrants more consideration of the analysis, and perhaps more data collection.