Assessing tough sustainability decisions: Informing expert intuition

Issues within an analysis

Photo © Ian Ellingham

The first issue with an analysis is that of time. Most human-produced goods are relatively short lived—packaging, domestic appliances, cars, clothing—but buildings and infrastructure, and their implications, can last centuries. The flows of resources associated with buildings (money, energy, CO2, shelter) occur at widely different times. How does one perform a comparative analysis of things happening in different decades?

Future uncertainty is also an issue. The world of sustainability is infested with uncertainties, simply because we cannot know the future. Unfortunately, much discussion about sustainability makes the tacit assumption the future can be predicted with some accuracy. However, the track record of predictions regarding societal shifts is poor. One might consider the projections of the economist W.S. Jevons (1835-1882), who stated the industrial economy would collapse as it ran out of coal. Accepting a lack of reliable knowledge about the future forces the decision-maker to attempt to identify and discern the nature of the uncertainties likely to affect outcomes.

As one looks further into the future, things become progressively more uncertain. While we can make reasonable assumptions about conditions a few months in the future, in 10 or 20 years things are quite hazy. Twenty-five years ago, few people would have predicted the massive changes resulting from the Internet or its impact on our lives.

Hence, with respect to data, all that can be known with any degree of exactness is the initial situation. We might know, with some reliability, the costs of alternatives, and their very short-term implications, but even these costs can be undermined even by events between design and commencement of building operations. The decision-maker should attempt to understand how and why things might change, recognize the uncertainties and how to measure them, and make decisions recognizing that projections about a single future state will almost certainly be wrong.

Another issue is that in sustainability there is no single simple measure. Most analytical tools were derived from finance or economics, so are expressed in terms of money. However, if one conceptualizes resources on an abstract basis, the models remain a way of relating resource flows that might occur at different times. We expend (or do not expend) now in the expectation of someone receiving some benefit in the future. One can work these models on energy, CO2 emissions, natural resources, or anything else, although once one starts counting in multiple terms, one has to create relationships between them.

The basic analytical tool

Discounting, the usual tool for comparing uncertain events occuring at different times, has its origins in the evaluation of financial assets. Many practitioners of environmental analysis tend to dismiss discounting. The reason for this is discounting is often misunderstood. It has its roots in the finance industry, and the decision-maker needs some insights into how discounting is applied in the context of the built environment. Discounting is often used to assess short-life products where time and uncertainty have limited roles relative to most consumer goods, but buildings are different because of their long and uncertain lives. If one ignores time and future uncertainty in decision-making, an event that might take place 1000 years in the future has the same weight as one happening tomorrow.

There are issues with discounting-based analysis, but recent refinements make it possible to use the method to gain better-quality insights into how to make decisions. The key factor in discounting is the rate, a number applied to uncertain future events to equate them to assured events in the present.

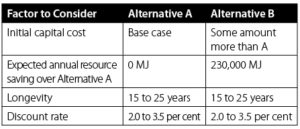

To illustrate how discounting can be applied, consider a simplified example where there is a choice between two pieces of mechanical equipment (Figure 1). One piece of equipment costs more, but offers ongoing savings in energy consumption, or some other resource flow. Without some reflection, the decision-maker might simply multiply the annual savings by some single life-expectancy, not recognizing the exposure of the decision to the life of the system.

But the decision-maker does not know how long the equipment will last. If the use of the building or space changes, it might be retired long before it wears out. To attach some values to the example, let us say Alternative B saves 230,000 MJ of energy per year, compared with a more basic and cheaper Alternative A. The expected longevity of the equipment is 15 to 25 years. After 15 years, with no discount applied, Alternative B saves 3.4 million MJ. With a discount of 3.5 per cent to allow for risk, the savings would only be valued at 2.6 million MJ (Figure 2, page 80).

In discount-based analysis, what initially may appear as a single discount rate actually resembles a multilayer sandwich: a convenient assemblage of elements that makes numerical analysis reasonably tractable. These elements include:

- Fundamental time preference. This reflects a desire for value now rather than later, in a very simple, risk-free environment. This is rather like putting money on guaranteed deposit with a bank. We expect that with the interest earned we will have adequate compensation for not receiving the expected benefit of spending now.

- A less obvious component relates to the expectation of increased well-being over time. This is of particular importance when considering sustainable investment. This encompasses all those things that have, over the past few centuries, contributed to increased human well-being, including improvements in technologies.

- Beyond this is an allowance for societal risk, acknowledging society may not exist in a state to collect the future benefits of an investment. This includes such possible catastrophes as natural disaster, thermonuclear war, or societal collapse.

Social discounting is different than private sector discounting, as it relates to a wider circle of concerns, not the individual uncertainties associated with a company or a particular asset. In corporate settings, discount rates are much higher, usually because they include a large factor to deal with specific (or unique) project or corporate risk.

Thus, discount rates provided by company accounting offices should be viewed with some skepticism for purposes of sustainability decisions.

One source of estimates and insights into decision-making for the wider population is the British government guide to the assessment of policies, projects, and programs, entitled “The Green Book: appraisal and evaluation in central government.” It suggests the use of 0.5 per cent per year for fundamental time preference, 1 per cent for catastrophic risk, and 2 per cent to account for the wealth effect. This suggests investments made for the benefit of society are subject to a relatively low discount rate. A rate of 3.5 per cent is reasonable, and is generally accepted as the Social Time Preference Rate by the government of the United Kingdom, although the document does not oppose the use of a lower rate.

Do you accept this? Perhaps not, but understanding the factors that have to be dealt with in considering future resource flows can be helpful in itself.