Assessing thermal performance and resiliency of contemporary buildings

Definitions of R-value

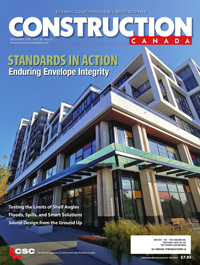

Photo courtesy Schokbeton Saramac

There are many different definitions of R-value, many of which were developed more than 20 years ago. The definition applied depends on the standard, code official, and the different needs of energy modellers and designers. However, the most important distinctions between the definitions involve how thermal bridging is considered.

When heat moves through an enclosure element, it flows through more than just the centre of the panel. Additional heat will flow through areas of steel or concrete penetrating the insulation layer. Such penetrations, termed thermal bridges, are inevitable and codes increasingly require designers to account for them when judging compliance.

Several types of R-values are reported in the industry or demanded by codes. These are explained below.

Installed R-value

The installed R-value, or nominal R-value, is simply the rated R-value of the insulation products in their installed condition (e.g. compressed batt insulation or not). The contribution of other materials is ignored.

Assembly R-value

The assembly R-value or centre-of-cavity is calculated by assuming the assembly is one-dimensional and simply adding the thermal resistance of all layers (e.g. in a precast concrete double-wythe insulated ‘sandwich’ panel, the outer concrete, insulation, inner concrete, and air films).

Clear-wall R-value

The clear-wall R-value (Rcw) accounts for the thermal resistance of the layers (assembly R-value). It also includes the two-dimensional effect of standard repetitive framing (e.g. steel studs and tracks) and conductive penetrations (e.g. floors).

Whole-wall R-value

The whole-wall R-value (Rww) includes Rcw and the thermal impact of any additional framing or fasteners at openings (e.g. windows and doors) as well as the effects of thermal bridges at changes in plane and other interfaces (e.g. foundation-to-above-grade-wall, wall-to-roof, and balconies) but excludes window area. For simplicity, sometimes the clear-wall R-value is used when whole-wall R-value should be (i.e. thermal bridging is ignored), but this approach can significantly overestimate the thermal performance of many commercial enclosure systems.

Overall

The overall R-value measures the performance of an entire enclosure type (such as wall or roof) and includes the combined effect of Rww and the heat loss through windows, doors, and curtain walls. It is important for understanding overall building performance and is implicit to the simple trade-off methods used to demonstrate compliance.

Effective R-value

The effective R-value is not a universal term, but rather is used to describe an R-value that may include some or all thermal bridging, air leakage, or even thermal mass. There is no one definition and it is not consistently used by major energy standards, but it is often the clear-wall R-value that is implied. Hence, the meaning of effective R-value varies depending on both the user of the term and the context.

Any of these R-values might also be reported as a U-value (U = 1/R). However, to add to the complexity, U-values almost always include the resistance of surface films, whereas R-values may or may not. Therefore, building professionals must be careful when interpreting requirements and be specific and precise when communicating required thermal performance.

Conclusion

Photo courtesy CPCI

More insulation, better airtightness, and less thermal bridging will be required by future codes and green building programs regardless of the type of enclosure wall system considered. Some jurisdictions have indicated a desire for energy codes to provide a path to net-zero ready performance. Since building codes offer several compliance paths, there is no one R-value that is required for a specific building in a particular location. Increasingly, trade-off compliance paths are often chosen. This allows for lower, sometimes significantly lower, enclosure wall R-values than listed in prescriptive tables.

Precast concrete systems are well placed to respond to the demand for higher thermal performance, as a broad range of R-values can be provided by changing design details (For more information on the thermal performance of precast concrete enclosure systems, read “Meeting and Exceeding Building Code Thermal Performance Requirements for Precast Concrete Walls” guide by RDH Building Science).

The “Meeting and Exceeding Building Code Thermal Performance Requirements for Precast Concrete Walls” guide presents the concepts at an introductory level for use in the early-stage design of precast concrete enclosure systems. Users should approach the guide by first calculating the clear-wall R-value for the system and floor-to-floor height under consideration, including thermal bridging of light-gauge steel framing and floor slab intersections. The insulation thickness and type can be adjusted as needed so the calculated value meets target design values or code minimums.

With prescriptive design, these values are sufficient, but alternate code compliance paths may make use of the values calculated for the selected enclosure design. The methods presented are not onerous to use and sufficiently accurate for early-stage design decisions. More detailed computer-based modelling will often be justified for complex systems, accurate results, and final design values.

The Canadian Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI) has worked with RDH Building Science and is launching the Precast Concrete Wall Thermal Performance Calculator. This new, online tool provides designers, builders, and owners with a program to quickly estimate thermal performance of precast concrete wall systems using the methodology described in RDH’s thermal performance guide. For this software, the influence of dynamic thermal mass, which can only properly be assessed using computer programs for a specific building location, design, and occupancy schedule, has been excluded. As a result, the calculations can be considered conservative in this respect since dynamic thermal mass effects help reduce energy use. CPCI’s tool can inform early design stage decisions by allowing users to quickly select and view the performance of common walls with varying types and degrees of insulation.

John Straube, PhD, P.Eng., is a principal at RDH Building Science and a cross-appointed faculty member in the School of Architecture and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Waterloo. He is also a prolific writer and a noted public speaker. Straube’s leadership as a building scientist and an educator has been recognized with multiple awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award in Building Science Education from the National Consortium of Housing Research Centers (NCHRC). He can be reached at jfstraube@rdh.com.

John Straube, PhD, P.Eng., is a principal at RDH Building Science and a cross-appointed faculty member in the School of Architecture and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Waterloo. He is also a prolific writer and a noted public speaker. Straube’s leadership as a building scientist and an educator has been recognized with multiple awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award in Building Science Education from the National Consortium of Housing Research Centers (NCHRC). He can be reached at jfstraube@rdh.com.

Brian J. Hall, BBA, MBA, is the managing director of the Canadian Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI), the vice-chair of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) Foundation, and a board member of the Athena Sustainable Materials Institute. He is one of the authors of the institute’s sustainability strategy that includes the development of the CPCI Precast Concrete Life Cycle Assessment, the Sustainable Plant Program, and the CPCI North American Environmental Product Declaration for precast concrete. Hall can be reached at brianhall@cpci.ca.

Brian J. Hall, BBA, MBA, is the managing director of the Canadian Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI), the vice-chair of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) Foundation, and a board member of the Athena Sustainable Materials Institute. He is one of the authors of the institute’s sustainability strategy that includes the development of the CPCI Precast Concrete Life Cycle Assessment, the Sustainable Plant Program, and the CPCI North American Environmental Product Declaration for precast concrete. Hall can be reached at brianhall@cpci.ca.