Assessing thermal performance and resiliency of contemporary buildings

Building codes

Building codes across North America define the lowest performance designers are legally allowed to provide. Owners and various green building standards routinely set higher targets. The most common energy standards referenced by Canadian building codes are NECB (2011 or 2015 edition) and versions of ASHRAE 90.1.

The Ontario Building Code (OBC) provides several options in Supplementary Standard (SB) 10, “Energy Efficiency Requirements,” and Québec is governed by the Regulation Respecting Energy Conservation in the New Buildings Act.

Provinces update their building codes every few years. Therefore, designers should check current building codes and any related amendments. It should also be noted variances exist in how local jurisdictions interpret building code requirements and these differences tend to evolve over time in unpredictable ways. Hence, the energy guides are intended for early design stage decisions and professionals with knowledge of local interpretations should perform actual compliance calculations as the project nears permit application.

Code compliance paths

There are several paths designers can use to demonstrate compliance, including:

- prescriptive;

- trade-off; and

- whole-building energy modelling (performance path).

Prescriptive

This compliance path involves following the prescriptive requirements of each section of the code. The local building permit office may require project teams to complete and submit a checklist as part of the permit application.

Trade-off

This compliance path provides some flexibility by allowing certain elements within the same part of the code to be traded. For example, if the design calls for more window area than prescribed by limits in the code, one may be able to compensate by improving the insulation in the walls. Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) offers downloadable trade-off path calculation tools to help with this method.

Performance

This approach offers the most design flexibility. One must show the proposed design will not consume more energy than an equivalent building built to the prescriptive requirements of the code. For this compliance path, designers need to use a building-energy simulation tool.

As a result, buildings can be constructed with a wide range of window, roof, floor slab, and wall R-values. Thus, it is impossible to answer the question, “What R-value do I have to meet?”, because three primary compliance paths exist in all relevant building codes.

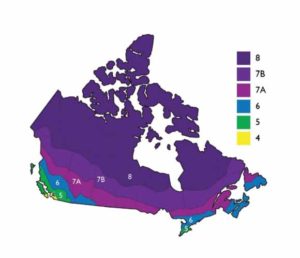

Climate

Regardless of the code, the climate in which the building is to be located plays an important role in understanding what energy-saving measures are required. The most commonly used climate categories employ a similar zone numbering system as codes in the United States.

Occupancy

Many codes require higher thermal performance for enclosures of residential occupancy than nonresidential. This is based on the assumption nonresidential occupancy will have higher internal heat gains from lights, equipment, and high occupant density. The semi-heated category is provided in some codes to account for attached storage areas, garages, and other spaces not required to be kept at room temperature.

Assembly construction

Several assembly construction types deliver thermal performance quite different from their standard rated R-value because of implicit thermal bridging or thermal mass. To account for this, codes often have different requirements for mass walls (made of concrete or masonry), light-gauge steel framing, pre-engineered metal building systems, and wood framing.

As codes have moved closer to describing whole-wall R-values, the need to define categories for different assembly types has diminished and NECB no longer has a category for mass walls. Ontario’s SB-10, in force from January 1, 2017, has set the maximum U-value for all types of enclosures to the same values in one compliance option, but allows ASHRAE 90.1 mass benefits in another.