Architects turn green for reliable and long-lasting roofing

by Katie Daniel | November 10, 2017 11:40 am

[1]

[1]By Stephen Knapp

When looking toward the sky in any major city in Canada and across North America, it is not uncommon to find a copper roof or wall cladding system. (For more information about the different types of copper applications, check out the Copper in Architecture Handbook[2].) The metal has contributed to elaborate ornamental applications and complex architectural details on historic buildings for centuries, but why do architects and design teams continue to specify this material? One reason is while all structures experience wear and tear over time, architects and contractors can trust copper will not deteriorate or corrode with age. As a result, this metal is installed on buildings designed to last a lifetime.

For the past decade, the Canadian Copper and Brass Development Association (CCBDA) and Copper Development Association (CDA) have held the North American Copper in Architecture (NACIA) awards program to highlight building projects in Canada and the United States that utilize significant architectural copper and copper alloys in their designs. The 2017 program showcases a wide range of projects, including three Canadian buildings that received new copper roofs: the Saskatchewan Legislative Dome Restoration project, the Centre Block of the Canadian Parliament, and 180 Wellington Street in Ottawa. (To view past recipients of the North American Copper in Architecture Awards [NACIA] program, visit the Copper Development Association’s [CDA’s] website at www.copper.org[3].)

These structures reveal the metal’s versatility. Copper is often used because it is extremely malleable—it can be formed, bent, and stretched into complex and intricate surfaces without breaking. This makes it possible to easily create spires, steeples, domes, nonlinear roofs and walls, and complicated dormers and fascia. These attributes have given building professionals the opportunity to expand their creativity.

Saskatchewan Legislative Dome

Recently, the Saskatchewan Legislative Dome in Regina—a 2017 NACIA award-winner—underwent a complete restoration of its copper dome roof system, which was originally constructed in 1912. The work included 12,700 kg (28,000 lb) of new copper and approximately 557 m2 (6000 sf) of roof surface area. The refurbishment included some existing copper decorative elements such as the cupola.

Most of the original 1912 framing and materials remained. The building had shifted during its more than a century of use, and the dome’s curvature was originally slightly out of alignment. This was challenging as the base structure supporting the copper needed substantial wood reframing over the concrete structure before reinstalling new copper. The original copper panels had loosened due to wind uplift after 100 years of service; it was allowing some moisture ingress into the original wood framing, which was inadequate in many areas.

The project was completed over a two-year period between 2015 and 2016, and every effort was made to conserve much of the original copper, including some of the intricate ornamentation such as the garlands, which were carefully removed and refurbished, as well as elements of the cupola and lantern areas. The building and grounds are designated as a National Historic Site of Canada and a Provincial Heritage Property. The protection ensures any repairs or improvements fully respect its heritage value and architectural integrity. The use of copper was consistent in type and form with the original materials used to complete the 1912 structure. Additionally, the design team selected the material for its durability and longevity.

The new copper was installed on a new insulated wood sub-roof system using a multitude of practices and standards such as cleats, clips, locks and soldered joints in accordance with The Copper in Architecture manual published by CDA.

[4]

[4]Patina

Although the dome appeared shiny when installed, typically, when left unprotected, copper and its principal architectural alloys naturally oxidize. This causes the metal to change in hue from the natural salmon pink colour through a series of russet brown shades to light and dark chocolate browns. From there, it will develop a dark, dull slate grey or dull black from which the ultimate blue-green or grey-green patinas emerge. Hues can vary from panel to panel, or even within the bounds of a panel.

In seacoast or industrial atmospheres like Regina, the natural patina generally forms in seven to 10 years. In rural atmospheres, where the quantity of airborne sulphur dioxide is relatively low, patina formation may not reach a dominant stage for 15 to 25 years. In arid environments, the basic sulphate patina may never form because the environment lacks sufficient moisture to carry the chemical conversion process to completion. The protective chemical reaction occurs when a corrosive attack of airborne sulphur compounds leads to a gradual change in the surface color until equilibrium is reached and the change is stabilized.

Centre Block

Another example of copper’s longevity is the Centre Block of the Canadian Parliament Buildings, which is one of three Gothic Revival sister buildings forming Parliament Hill in Ottawa. It is also a Classified Federal Heritage Building and arguably the most important example of Canadian Heritage architecture. The latest structure, built between 1916 and 1927, has always maintained its character-defining copper mansard roofs, cresting, and decorative elements.

A major component of the East Pavilion Rehabilitation Project was the replacement of the existing copper batten roof, dormers, and all ornamental copper cresting, including finials that had either reached the end of their life cycle or were missing. Each component was replicated in kind with the original design and construction, honouring the heritage value of the building fabric. Where necessary, minor changes were incorporated into the building’s design to improve the durability and decrease the risk of deterioration to the existing roof structure.

Alloys

Achieving these desired esthetics does not require sealers or paints. A wide variety of copper alloys are available for architectural use, including bronze, brass, copper nickel, and nickel silver are primarily used for decorative installations on the exterior and interior of buildings. These copper alloys are strong, lightweight, malleable, and highly corrosion-resistant, and thus are ideally suited for roofing applications. However, bronze, brass, copper nickel, and nickel silver are primarily used for decorative installations on the exterior and interior of buildings. When properly designed and installed, a copper roof provides an economical, long-term roofing solution. Its low life cycle costs are attributable to the low maintenance, long life, and salvage value of copper. Unlike many other metal roofing materials, copper requires no painting or finishing. Its natural patina eventually covers the surface, adhering tightly and providing a protective layer against weathering.

When considering typical copper systems, designers should reference ASTM B370, Standard Specification for Copper Sheet and Strip for Building Construction. This standard defines composition, dimensional tolerances, and mechanical properties. This family of metals can be the solution for many innovative building designs, especially those seeking to accentuate the natural environment.

The specified slider does not exist.

[5]

[5]Photos courtesy Doublespace Photography

180 Wellington St.

Like all materials, copper will not last forever, but unlike other materials, its benefits do not end once construction is completed. In fact, a major benefit of copper’s use—total recyclability—is realized during demolition. Further, nearly all of the copper ever mined is still in use today. It is one of the most easily recycled metals available.

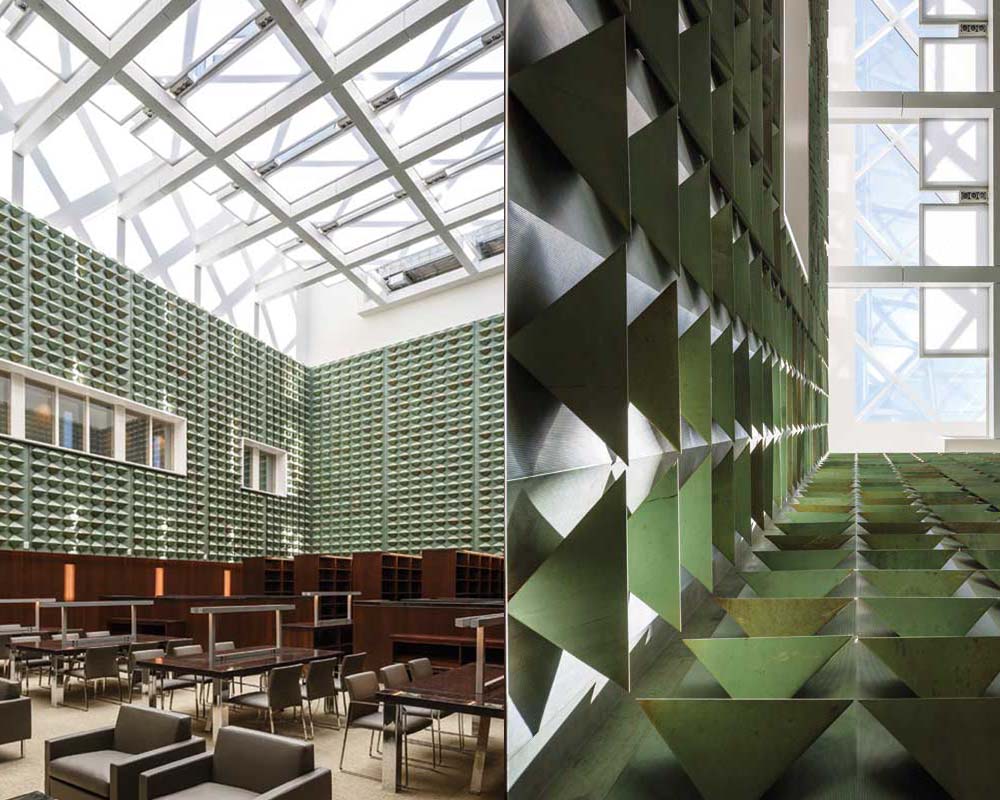

The design team of 180 Wellington St., an adaptive reuse of a 1920s office building for members of the House of Commons of Canadian Parliament included NORR Architects and Engineers and EllisDon Constructors. They took advantage of copper’s recyclability when refurbishing its roof, which needed to be replaced after 60 years of providing shelter. Although new copper was installed on the roof, the previous material was removed with great care, stored, and sorted for reuse in the design of a sculptural wall component in the Library of Parliament.

To provide the sound attenuation and sculptural finish for the walls of the library, 1208 m2 (13,000 sf) of aged copper was cut from the existing roof, crated, sorted, flattened, perforated, and then bent on a break press. The folded, perforated aged copper lining and the folded, sculptural aged copper shells take their inspiration from the triangulated roofscape of the Parliament Hill government buildings. The fabricator handling the sculptural wall was Mometal Structures Inc.

Copper’s pleasing esthetic qualities ensure designers can achieve their visual aspirations while also meeting important environmental and cost-performance objectives. Going green is not just a trend. With an increase in demand for natural resources, many builders are realizing the importance of sustainable building principles.

Conclusion

As the material of choice for many historic and traditional types of architectural systems and structures, copper is increasingly being used for a wide variety of new and exciting contemporary installations.

The metal offers esthetically stunning qualities along with unique physical and mechanical properties. This ensures designers and building owners not only achieve their visual aspirations and performance specifications, but are also able to meet their environmental and cost-performance goals. While nobody can predict exactly what the building and construction market will do in the future, it is evident copper will remain an important building material for years to come.

Stephen Knapp is the program manager of the Sheet, Strip, and Plate Council for the Copper Development Association (CDA), and executive director of the Canadian Copper and Brass Development Association (CCBDA), the national trade association in Canada for the copper industry. Knapp is also involved with guiding the market development and promotional efforts for a wide variety of copper and copper alloys applications, such as tube and plumbing, electrical, and renewable energy systems, as well as energy-efficiency technologies. He can be reached via e-mail at sawknapp@coppercanada.ca[6].

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Ministry-of-Central-Services-Government-of-Saskatchewan-1.jpg

- Copper in Architecture Handbook: https://www.copper.org/publications/pub_list/pdf/A4050-Architectural-Handbook.pdf

- www.copper.org: http://www.copper.org

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IMG_5421.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/edit1.jpg

- sawknapp@coppercanada.ca: mailto:sawknapp@coppercanada.ca

Source URL: https://www.constructioncanada.net/architects-turn-green-reliable-long-lasting-roofing/