Affordable Shine: Reflective alternatives to diamond-polished concrete floors

by Elaina Adams | January 1, 2012 1:58 pm

[1]

[1]By Brad Sleeper and Steven H. Miller, CDT

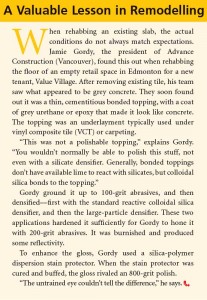

The sheen of the floor in an Edmonton Value Village store may look like polished concrete, but it is, in fact, neither polished nor concrete. The surface material is actually a bonded topping—a relatively soft cementitious material used as underlayment for carpet or vinyl tile, which would not normally be considered ‘shinable.’ Instead of the labour-intensive finish made by polishing it with fine diamond abrasives, it was honed with only medium-grit abrasives, hardened with an advanced-chemistry densifier, protected with a breathable sealer, and buffed to a near-polished shine—a much more affordable treatment.

Since the introduction of diamond-polished concrete floor systems in the 90s, demand for glossy concrete floors has grown enormously. However, the desire for a reflective concrete floor often outstrips the available budget. Diamond grinding and polishing can be costly, both because of labour and the consumable diamond-impregnated tools.

In response to the need for more affordable reflective concrete floors, necessity has given birth to invention. Advancements in chemistry and abrasives have been the focus of experimentation by resourceful contractors. They have developed several fast, economical methods of putting a reflective surface on concrete without diamond polishing by taking advantage of certain unique properties of a chemical compound called reactive colloidal silica. (Silica is more properly known as ‘silicon dioxide’—the hard mineral compound familiar in its crystalline form as quartz or beach sand.) These floors provide the performance and decorative options of polished concrete at a price point well below diamond polishing—sometimes 65 per cent less. In many cases, their gloss is indistinguishable from a true polish to the untrained eye.

[2]

[2]Decorative concrete: a grassroots revolution

Development of new decorative concrete methods and products has been driven by practitioners—applicators, finishing contractors, and artisans. When one talks to the people who founded numerous companies manufacturing decorative concrete products, the same story is repeated with startling fidelity:

- They started as contractors, working in the field making things out of concrete, and constantly struggling to get the right result using the accepted practices of the day. They thought, “There has to be a better way.”

- They took a risk, modified materials, improved methods, and got results that nobody had ever seen before.

- Other practitioners began asking how they did it, so they gave lessons.

- They began selling their own concoctions to their students and, suddenly, they were manufacturers.

The next step, of course, was their students began innovating, inventing, and creating the next generation of new looks and applications. Demand for exposed concrete floors and other architectural surfaces and objects—countertops, sinks, fireplaces, and furnishings—continues to bring talented contractors into decorative concrete, even in a down economy, because the concrete option is often more affordable and more sustainable than traditional alternatives. Therefore, innovation has continued to grow, even as budgets have slumped.

[3]

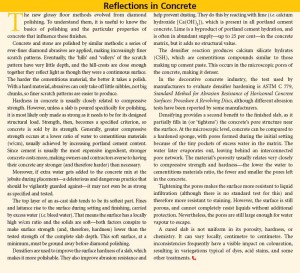

[3]The (re)active ingredient

The glossy exposed concrete floor is becoming more common, with diamond polishing being the traditional means to achieve it. In an era when budgetary pressure is even greater than usual, however, innovation has been driven in the direction of finding ways to offer glossy floors at lower cost. In this context, the peculiar properties of reactive colloidal silica, a water-based suspension of almost pure silica, have proved very exploitable. (Colloidal silica is amorphous silica, and should not be confused with crystalline silica and its associated health risks. Crystalline silica is present in concrete, however, and appropriate protection against inhalation of silica dust should always be used when grinding or polishing any concrete). It is used as a densifier, and is also included in several other products connected with exposed concrete floor finishing.

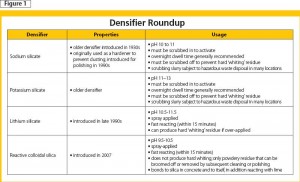

Densifiers are chemicals that react with lime in the concrete to produce new cementitious material. It partially fills, or ‘tightens,’ the concrete pore structure as shown in Figure 1. To improve wear-resistance and minimize dusting, densifiers have been used for decades (often under the term, ‘hardener’) on exposed slabs that were not being given decorative treatment. They were introduced for a new purpose in the mid-1990s—concrete polishing. First came sodium silicate and potassium silicate, then lithium silicate in the late 90s, and reactive colloidal silica five years ago.

Reactive colloidal silica was not invented for use in concrete; rather, it was discovered by two polishing contractors who found it superior to the silicate densifiers they had been using. Unlike sodium silicate and potassium silicate, it does not have to be scrubbed in or off. Spray-applied and dry within an hour, it requires no overnight dwell time, and does not produce a caustic residue subject to hazardous waste disposal restrictions.

[4]

[4]Unlike a mishandled silicate, reactive colloidal silica does not produce whiting—a hard residue that would have to be ground off, essentially starting the polishing process over. It is also lower in pH, making it safer to handle. Still, the most versatile advantage turns out to be the ability of reactive colloidal silica to bond to other silica, including itself. It not only reacts with the lime in concrete, but also bonds to the cement’s silica. Silica in suspension will also bond to silica that has already bonded to the concrete, allowing it to accumulate. This bonding and buildup property does not occur in any of the silicates.

Applicators using reactive colloidal silica as a densifier noticed a floor that had been ground smooth could be buffed to a nice sheen even before it was fully polished. They realized they were getting the gloss from the densifier buildup. This discovery led to numerous new methods of finishing floors using reactive colloidal silica in two different types of product: densifiers and stain protectors.

The latter is a category of breathable sealers that should always be used to complete polished concrete applications. Even after densification, concrete surfaces remain somewhat porous, and can still be infiltrated by liquids. Conventional stain protectors (their brand names often include the words, ‘protector,’ ‘guard,’ or ‘shield’) are one-part polymer solutions that deposit a thin, breathable protective layer on the concrete surface, usually darkening the colour slightly and imparting a slightly wet look. This application eventually wears off and needs to be re-applied. Wear time depends on both product quality and traffic conditions, and may be as little as six months or more than two years.

[5]

[5]Grind but don’t polish

One new method for putting shine on the concrete is to grind the floor smooth, and then employ a specialized large-particle densifier to build up a surface that can be glossed (rather than proceeding through the usual steps of full polishing). The floor is diamond ground up to the 100-grit abrasives. It is then densified twice. The first is a standard colloidal silica densifier with silica particles on the order of 5 nanometers (i.e. 0.000005 mm [0.0002 mils]) in diameter. This reacts with the concrete, but also lays down a silica ‘landing pad’ that will acquire greater buildupon further applications.

The second densifier is also colloidal silica, but the particles are much larger, on the order of 40 nanometers. This larger particle size provides a greater silica buildup on the surface. This buildup is then burnished to a reflective surface—meaning it displays well-defined, realistic reflections of brightly lit objects—using a high-speed burnishing machine fitted with a hogs-hair pad (a common cleaning accessory).

The floor is then treated with a stain protector that contains a polymer, along with reactive colloidal silica. The latter helps the former bond to the silica already in the slab, and brings additional silica to the wear surface. The application dries in about 15 minutes. Burnishing it again brings up more reflectivity, and performs a second, equally important function—the friction-induced heat of burnishing helps cure the polymer faster and harder.

This method adds reflectivity to the surface without the time and expense of diamond polishing. It does not require the machines, diamond consumption, and heavy power usage of full polishing. The floor should be maintained using a cleanser containing reactive colloidal silica that fortifies surface hardness with additional silica, extending the stain protector’s service life and helping restore the original shine when re-buffed.

[6]

[6]The same method can be applied to polishable self-levelling cementitious overlays. (These materials will be discussed in more depth later in this article.) However, with reference to projects involving grinding of polishable overlays, one should inquire with the overlay manufacturer for any technical bulletin on grinding and polishing, in addition to the standard product data. Special instructions sometimes apply, such as dry—and not wet—grinding.

Don’t even grind

In some situations, even the coarse grinding steps can be eliminated in the quest for a glossy floor. On a power-trowelled concrete floor in good condition, a durable reflective finish can be created by cleaning the slab with sanding screens (a cleaning tool mounted on a rotary scrubbing machine or ‘autoscrubber’), using a combination of specialized densifiers and stain protector, and burnishing.

This strategy was adopted for a 20,070-m2 (216,000-sf) single-storey facility used for assembly of high-tech avionics equipment. The facility had strict operating conditions, such as humidity controlled at 78 per cent, and high attention to cleanliness. It was also frequently visited by customers. The owner wanted a glossy, high-appearance floor with good reflectivity, no dusting, easy maintenance, and a long service life.

[7]The newly placed slab was power-trowelled by the placement contractor, and the surface was highly consolidated. Once cured, it was cleaned with sanding screens. After applying the first, standard-particle-size reactive colloidal silica densifier, the floor was cleaned with an autoscrubber. Then the large-particle densifier was applied. When it was burnished with a black stripper pad, the gloss appeared. It was coated with a colloidal silica-based stain protector and burnished again to further enhance reflectivity and speed up curing.

[7]The newly placed slab was power-trowelled by the placement contractor, and the surface was highly consolidated. Once cured, it was cleaned with sanding screens. After applying the first, standard-particle-size reactive colloidal silica densifier, the floor was cleaned with an autoscrubber. Then the large-particle densifier was applied. When it was burnished with a black stripper pad, the gloss appeared. It was coated with a colloidal silica-based stain protector and burnished again to further enhance reflectivity and speed up curing.

Another effective variant of this ‘no-grinding’ treatment uses only one densifier, but achieves gloss with a coating of the silica-polymer dispersion. This approach was used in the operations centre of a power utility. Once again, the trowelled concrete was cleaned with sanding screens on a high-speed burnisher. It was hardened with standard reactive colloidal silica densifier, which provided a ‘landing pad’ to bond with the silica in the polymer application. The silica-polymer dispersion was rolled onto a thickness of 0.025 to 0.035 mm (1 to 1.5 mils). Subsequent burnishing with a hogs-hair pad produced a shine.

After finishing, the floor was used to store materials for the mechanical shop. Residues accumulated, and the floor became slippery. The general contractor requested the residue be removed, which required high-speed burnishing with medium-grit a diamond-impregnated pad. The expectation was that this process would remove the stain protector finish and re-application would be required. The silica polymer dispersion proved to be tough enough

to resist this treatment, which actually improved both reflectivity and traction.

[8]

[8]a smooth, but not glossy, finish sometimes called ‘honed.’ It was dyed, densified with reactive colloidal silica, and burnished before being treated with silica-polymer dispersion stain protector, which bonds to silica in the densified surface. After a second burnishing, it became the intriguing, reflective floor seen here.

Don’t even trowel

There is a new generation of self-levelling cementitious overlays that cure rapidly—within a few hours—to a surface hard enough to polish. They can be diamond-ground, coloured, densified, and polished into a new, lustrous floor the day after they are poured. They can be poured onto existing concrete, even if it is badly damaged, in thicknesses ranging from 3 to 50 mm (1⁄8 to 2 in.). These materials are compatible with integral colour and concrete dyes. Many of them are bright off-white in their natural state, forming a brighter base for colours than grey concrete. (A light-coloured floor may have the added benefit of reducing illumination-energy consumption by providing higher light reflectance.) In remodelling projects, overlays can save considerable expense compared to grinding a damaged floor down until good concrete is revealed.

Some self-levelling overlays can also be processed to a reflective shine in their as-poured state, with no grinding whatsoever. (To aid in curing, some overlays form a polymer cap or skin on the surface. This resists densifier or dye, and needs to be ground off before densifying or dyeing can proceed. When specifying an overlay material for a non-grind finish, one should specify a product that does not form a polymer cap). This is one of the fastest methods available for creating a glossy cementitious floor. It is accomplished using densifier and an advanced formula stain protector—a two-part silica-polymer dispersion that builds up a thicker polymer layer than conventional materials. It is a waterborne modified epoxy that is self-levelling, curing to about 0.025 mm(1 mil) thickness and fortified with reactive colloidal silica densifier. This silica content imparts a glossability to the stain protector not seen in conventional polymer protectors, and improves its toughness and bond strength for greater durability. There is no standardized durability test for this type of material, but field tests suggest silica-polymer dispersion lasts perhaps twice as long as conventional stain protectors before re-application is required.

The as-poured surface of a polishable self-levelling overlay is usually flat and smooth enough to become a finished floor. It can be made glossy and durable through treatment very similar to the as-trowelled concrete. The steps are simple:

- pour overlay, either in its natural look or integrally coloured;

- allow to cure;

- dye if desired;

- densify with colloidal silica to form silica ‘landing pad;’

- apply silica-polymer dispersion; and

- burnish with hogs-hair pad.

For a moderate-sized retail facility of about 450 m2 (5000 sf), this method can reduce the total time from overlay pour to completion by about 40 per cent. The overlay pour itself can take about four hours, and should be allowed to cure overnight before further work on it. Densifying and silica polymer dispersion application is about six hours, and should be allowed to cure overnight (at least 12 hours). One hour to burnish the following day completes the job. By contrast, doing a full diamond polish would add an entire additional day for a three- to four-person crew. However, prep time before overlay pour can widely vary, depending on the floor’s initial condition.

[9]Some of the polishable overlays are based on calcium aluminate cements (as opposed to portland cement) that have very strict and unforgiving water demands. If liquid pigment dispersions are used for colouration, one must ascertain from the overlay manufacturer whether mix water needs to be adjusted to compensate for the added liquid.

[9]Some of the polishable overlays are based on calcium aluminate cements (as opposed to portland cement) that have very strict and unforgiving water demands. If liquid pigment dispersions are used for colouration, one must ascertain from the overlay manufacturer whether mix water needs to be adjusted to compensate for the added liquid.

Due to the highly modified mix design of self-levelling overlays, reactivity of silicate densifiers is reduced. Overlays based on calcium aluminate cements have the least reactivity with silicates since these cements do not produce large quantities of lime during hydration, leaving densifiers little or nothing with which to react. However, overlays contain significant quantities of fumed silica that react with colloidal silica to increase abrasion resistance, independent of the lime reaction. This makes it possible to build up a gloss, even in a slab where a silicate densifier may be ineffective.

Conclusion

New materials frequently get invented to improve results of established best practices, but they often give rise to new and better ones. The decorative concrete industry has been a hotbed of technological and creative innovation with its genesis on the jobsite, as practitioners constantly push the limits of available products, and create new ones.

Among the chief beneficiaries of this innovation are designers. Results can now be achieved in concrete that greatly enlarge the range of choices. The methods described here have more in common than just the utilization of certain properties of reactive colloidal silica; that is, they are all the products of contractors finding better ways to meet their customer’s needs within tight budgets and time constraints.

Since so much innovation comes from the field, designers interested in using decorative concrete are advised to keep watching the industry closely, reading technical magazines and blogs, and going to decorative concrete shows. There are horizons to be broadened and inspirations to be found.

Brad Sleeper is vice-president of sales and marketing and co-founder of Lythic Solutions, a concrete polishing and finishing technology company. He is also a professional concrete and stone polishing contractor, with more than a decade of experience in the field. Sleeper can be contacted via e-mail at brads@lythic.net

Steven H. Miller, CDT, is an award-winning writer and photographer specializing in issues of the construction industry. He is creative director at Chusid Associates, a marketing and technical consulting firm serving the building products industry. Miller can be reached via www.chusid.com.

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Korry2-corr.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/2011-09-21_10-44-39_118-corr-crop.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Eweb-shop-corr.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/table-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/photo-1-lrg.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/VV-cleaning2-corr.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/reflections.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/applewood-1-crop.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/valuable.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructioncanada.net/affordable-shine-reflective-alternatives-to-diamond-polished-concrete-floors/