Adoption of Passive House in British Columbia

Image courtesy MCM Partnership

By Andrew Larigakis, RIBA, AIBC, MRAIC, LEED AP

Government institutions are recognizing the role the Passive House standard can play in effectively reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and are beginning to introduce it into their requirements and codes for all types of new buildings (According to a statement released by the Passive House Institute (PHI) during the 2017 Climate Change Conference COP23 in Bonn, Germany, the United Nations (UN) explicitly mentions Passive House as a possibility to increase the energy efficiency of buildings and thus reduce global warming. ). While different levels of government in various jurisdictions are introducing regulations influenced by Passive House, British Columbia, and the City of Vancouver in particular, is currently at the forefront.

Though the Passive House standard has existed since the mid-1990s and tens of thousands of Passive House-compliant buildings have been constructed worldwide, one can only now see the standard and its approach to green building being embedded into government requirements and building codes outside Northern Europe.

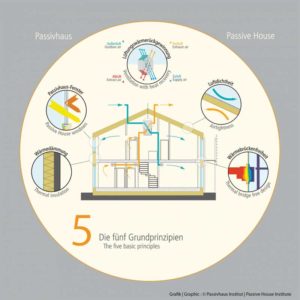

Though not rocket science, meeting the Passive House standard is not easy, and requires changes to the way one thinks about constructing buildings in North America. Instead of focusing on mechanical solutions—which have so far not delivered the promised levels of emissions reduction—the Passive House approach is more oriented to the building envelope. The method requires generous insulation, a high level of airtightness, thermal bridge-free construction, and high-performance windows with mechanical ventilation and high heat recovery efficiency.

Image courtesy Passivhaus Institut

Imposing regulations and providing incentives to apply the standard across the board has the potential for a notable impact on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions when compared to the current smattering of “green” projects that do not focus on energy efficiency.

At the federal level, Canada’s commitment under the Paris Agreement is to reduce the nation’s GHG emissions by 30 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030 and 80 per cent by 2050. At the forefront of the federal government’s policy is the “Greening Government Strategy,” targeting emissions from government operations. For new government buildings, the goal is to be net zero carbon-ready starting, at the latest, in 2022, and for all major building retrofits, the goal is to be low carbon. The government intends to introduce a “first tier” of stringent model codes for buildings in 2020 (Click here for Canada’s buildings strategy. ). The influence of building envelope-focused Passive House principles on these forthcoming codes remains to be seen.

British Columbia, though, recently introduced the Energy Step Code, a part of the B.C. Building Code (BCBC), providing effective Passive House-related standards for GHG reductions. The City of Vancouver has also set itself aggressive green building goals, supported by regulations and policies—including Passive House—as a path to compliance. Additionally, the City of North Vancouver is moving forward with its own requirements. This city’s most ambitious regulatory regime applies to the new Moodyville neighbourhood where Passive House forms a route for gaining approvals.