Addressing insulation challenges in cold regions

by Ted Winslow

Canada is a vast country with drastic differences in topography, rainfall, and humidity—all factors influencing the decisions of builders and architects when they are creating comfortable and energy-efficient structures. With nearly all of Canada sitting north of the 45th parallel, insulating homes, businesses, and industrial applications to achieve thermal efficiency is a persistent challenge. Thanks to long winters and cold temperatures, many of Canada’s structures are in a constant battle against energy loss.

There are many reasons for building professionals to be concerned about proper insulation. According to a recent report, Canada produces more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than any other G20 country. While a great deal of that is attributed to oil and gas transportation, much of it stems from the costs of heating and operating buildings in colder climates. For example, commercial buildings account for over 50 per cent of the country’s total electricity consumption and roughly 28 per cent of the nation’s GHG emissions, according to the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). According to Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), 80 per cent of residential energy consumption can be attributed to space and water heating alone. Canada is a vast country with drastic differences in topography, rainfall, and humidity—all factors influencing the decisions of builders and architects when they are creating comfortable and energy-efficient structures. With nearly all of Canada sitting north of the 45th parallel, insulating homes, businesses, and industrial applications to achieve thermal efficiency is a persistent challenge. Thanks to long winters and cold temperatures, many of Canada’s structures are in a constant battle against energy loss.

Proper insulation is crucial in mitigating long-term operating costs for building owners. It also goes a long way toward helping Canada meet its ambitious national goal of reducing GHG emissions to no more than 511 million tonnes by 2030 (down 70 per cent from 2005 levels).

Designing for thermal control

Temperatures vary widely from region to region. For instance, the average January low for Toronto is –10 C (14 F) while Winnipeg is –23 C (9 F). In Yellowknife, N.W.T., the average January temperature is a frigid –31 C (24 F). Designing for maximum thermal control should be top of mind for every builder and architect.

Additionally, it is critical to have a good understanding of heat transfer and thermal efficiency. Heat flows naturally from areas of high to low temperature. The bigger the temperature difference, the more the heat flows (or transfers) through an assembly. For example, a heated building will lose heat to its colder exterior in the winter, and in the summer, an air-conditioned building will draw heat from its warm exterior. In the makeup of walls, pipes, and other mediums, certain materials speed up the rate of heat transfer or hinder it. Conductors like metal transfer heat very well, while insulators like fibreglass have a high resistance to heat flow.

Conduction, convection, and radiation—the three modes of heat transfer—occur simultaneously and play an important role in balancing the thermal performance of a building. Conduction, or the transfer of heat energy through a substance or material takes place when a material separates an area of high temperature from a space with low temperature, such as a wall. Convection, forced or natural, happens when a liquid or gas moves over a surface, such as wind blowing against a building. Natural convection occurs when the movement of liquid or gas is caused by density differences. In forced convection, the movement of the liquid or gas is precipitated by external forces. Radiation involves the transfer of electromagnetic heat waves from one object of higher temperature (e.g. the sun) to another of lower temperature.

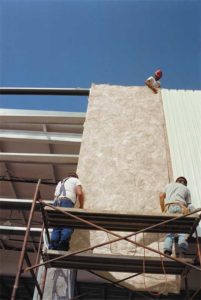

Structural components in buildings are highly conductive and create thermal bridges. For instance, metals conduct 300 to 1000 times more heat than most building materials. This means a metal stud has an exaggerated effect on heat transfer that is out of proportion to its physical size—even greater than the material’s actual surface area—making the selection of proper insulation assemblies crucial. To create a more energy-efficient and comfortable building, design professionals must find ways to ‘break’ thermal bridges to reduce the transfer of heat energy through the wall (or roof).

While heat transfer cannot be stopped entirely, it is possible to significantly slow down the process by placing appropriate obstacles in its path. Here are some ways to design with insulation in mind in various scenarios.