A reintroduction to acoustics

Understandably, the term ‘noise’ can cause confusion when the ‘signal’ is the unwanted sound and the ‘noise’ is actually the desired background sound. Meanwhile, the general public tends to use ‘noise’ as a non-technical descriptive word, typically when relating negative acoustical experiences—ones that are uncomfortable, annoying, disturbing, or even painful.

To highlight the difference in the way in which ‘noise’ is used, consider an individual working in an office, who complains about ‘noise’ to a colleague. There are several sources of sound within the space (exterior traffic, a fan, and a radio playing music), but the source bothering the individual is a heated debate taking place in the meeting room adjacent to their workspace. In this scenario, the terms are defined in this way:

- sound – there are four sound sources identified in the workplace.

- signal – the noise that is capturing the individual’s attention (i.e. the debate) and, hence the cause of their complaint.

- noise – the individual uses the word ‘noise’ to describe the debate. However, if the term is used in a technical assessment of this environment, the ‘noise’ is actually the combination of all other sound sources (i.e. the traffic, fan, and radio), excluding the signal (i.e. the debate).

Technical use of the word ‘noise’ requires a ‘signal.’ In this case, noise accounts for the combination of sounds (i.e. it considers everything that is not the signal), while the signal only considers the source of the sound that is of interest.

The human factor

What turns a ‘sound’ into a ‘noise’ in the common vernacular? Humans demonstrate remarkable tolerance to sound and are only susceptible to its disruptions when they become aware of it—typically when the level of sound is too high, its qualities are unbalanced (e.g. it is too ‘hissy’ or ‘rumbly’), or it presents with temporal instability of its dynamic range (i.e. the change and/or rate of change in sound level over time).

Photo © Jon Evans Photography

Context

A person’s assessment of sound generally depends on personal preferences and expectations for the occupied environment, as well as the activity in which they are engaged. For instance, consider a conversation at ‘normal level’ in two environments: a library and a busy restaurant. In the former, nearby occupants engrossed in a task requiring concentration are likely to find the conversation too loud, annoying, and disruptive. In the latter, the level of conversation may not be sufficiently loud to allow for clear communication. Expectations are based on an understanding of the purpose of the space and the task

at hand.

Content

One’s description of sound tends to focus on two main properties: its level (often referred to as volume) and its spectral distribution. A ‘hissy’ or ‘screechy’ sound is one that has a lot of high frequency information (e.g. a young child screaming). A ‘bassy’ or ‘rumbly’ sound is one with a lot of low frequency information (e.g. a lion roaring). A space without a balanced sound spectrum can sound worse than one with a higher sound level, but with a balanced spectrum.

Cover

The human experience is also determined by the space’s background sound level, which is considered to be the collection of all (ambient) sounds within it. Often, a room is too ‘silent’ (i.e. its ambient level is too low) and a source of sound becomes uncomfortable (e.g. a clock ticking, cars driving by, people talking, lights humming). In these cases, the ‘signal’ is disturbing because its level is higher than the background sound. The disruptive impact of these annoying noises can be lessened by reducing the signal-to-noise ratio, which is achieved by raising the background sound level. In some cases, it is possible to raise the background

sound level sufficiently to completely cover up these unwanted sounds.

The need for control

Given both the scientific and human factors, one can readily see there are advantages to controlling background sound, rather than accepting large variations in its level and spectra.

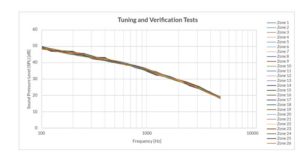

The consequences of neglecting this principal parameter of architectural acoustical design is an environment that is perceived to be ‘noisy,’ as presented in Figure 1. The alternative—to add sound to reduce the perception of a noisy environment—might seem counterintuitive, but consider Figure 2. By precisely controlling the spectrum and level of sound (in this case, to a target overall sound pressure level of 47 dBA), one can make the space sound more comfortable.