A reintroduction to acoustics

By Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng., and Niklas Moeller

Acoustics is a vital part of our everyday experience of the built environment; however, the role background sound plays in making these environments more comfortable for occupants is often overlooked. As a result, the misconception persists that acoustical dissatisfaction and lack of speech privacy can be resolved merely by limiting noise levels or blocking transmission.

Given today’s focus on health and wellness, it seems prudent to revisit our acoustical lexicon with the intention of developing deeper awareness of the differences between background sound and noise, as well as their implications for our experience within facilities.

Refining our understanding of ‘noise’ and ‘sound,’ as well as terms such as ‘silence’ and ‘quiet,’ fosters opportunities to improve building design practices and, hence, occupant well-being. Indeed, it is only by controlling background sound—in contrast to limiting background noise—that one can realize certain benefits, such as increased speech privacy and improved specification of construction requirements, as well as the associated labour and cost savings.

Architectural acoustics

The study of acoustics dates back thousands of years. Given its roots are deeply entangled with those of mathematics and physics, it is unsurprising the typical approach to acoustic investigation is quantitative. Consideration of ‘soft’ parameters (i.e. subjective and descriptive) is relatively scarce until the last century.

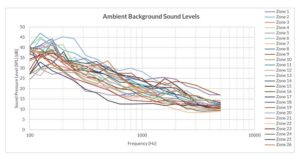

Images courtesy KR Moeller Associates Ltd.

Interest in evaluating human response to acoustics gained momentum in the 1900s, with the rise of architectural acoustics—also known as building or room acoustics. Most notably, contributions from Bell Telephone Laboratories, Bolt Beranek & Newman Inc., and others formed the foundation for psychoacoustics, a branch of psychology focusing on the perception of sound and its physiological effects. Research examined the occupants’ assessment of intruding noise (e.g. annoyance, distraction, inadequate acoustical privacy) in their environment.

Motivated by the need to develop an objective approach to effective architectural acoustical design, William Cavanaugh et al. published Speech Privacy in Buildings (1962), asserting neither acoustical privacy nor acoustical satisfaction could be guaranteed by any single design parameter. This work was instrumental in what became to be understood as the ‘ABCs’ of architectural acoustical design:

- ‘A’ is for ‘absorb,’ which involves providing sufficient, but not excessive, absorptive materials, in order to reduce the amount of sound energy within the space;

- ‘B’ is for ‘block,’ which involves providing sufficient isolation within the space; and

- ‘C’ is for ‘cover’—or one might say ‘control’—which involves management of the spectral distribution and overall level of background sound within the space, with the intention of masking speech and noise (rather than, for example, adding biophilic sounds, with the intention of increasing occupant connectivity with the natural environment).

Although the authors of Speech Privacy in Buildings appreciated the importance of background sound, they tended to use the words ‘noise’ and ‘sound’ interchangeably—a practice deeply rooted in historical habits, which continues today.

The signal-to-noise ratio

Initially, acousticians such as those at the Bell Telephone Laboratories were primarily interested in evaluating the conditions needed to clearly hear sounds. They determined the critical factor was the level of the desired sound—called the ‘signal’—relative to the background sound present in the listener’s location. In most cases, the background sound used during testing was broadband and did not contain information (i.e. noticeable patterns such as running speech, nature sounds, and traffic noise); however, it was termed ‘noise’ because it could potentially interfere with the intelligibility of the desired sound. The ratio of the desired sound to background sound was termed the signal-to-noise ratio.

In the above case, the ‘signal’ is the sound one wants to hear because it conveys useful information, while the ‘noise’ is an unwanted input challenging one’s ability to clearly hear the desired sound. As acousticians developed an understanding of background sound as a fundamental component of speech privacy, the methodology—and the terminology—remained the same. Hence, the word ‘noise’ continued to be used to describe the background—or, in this case, the masking—sound, despite the fact it was now being viewed in a positive light.