Urbanization is the leading growth catalyst for cities, economies, and technologies around the world. More than half the global population already lives in urban areas, and the United Nations estimates by 2030, five billion people will be living in cities—up from 3.6 billion in 2010. According to Statistics Canada, 81 per cent of the population already lives in urban areas—a figure rising steadily year after year.

Faced with unprecedented urban growth not seen since the early 1990s, architects, designers, and construction professionals are under pressure to make cities smarter and easier to live in. Adding to the urgency for innovative solutions is the increasing need for environmentally responsible technology. While cities cover less than two per cent of the planet, they account for 75 per cent of global energy consumption and 80 per cent of manmade carbon emissions.1

As these trends continue and the world’s population skyrockets, the model of the downtown work core with ever-expanding suburbs is becoming outdated. Many experts think the only sustainable solution is to create denser cities by building upward. While new technologies are needed across multiple industries to grow cities in the future, the next leap in building heights is difficult without a corresponding rise in elevator technology.

No limits

Chicago’s Homes Insurance Building is considered to be the world’s first skyscraper. Built in 1884, it stands at 42 m (137 ft) and 10 storeys tall, and was also the first structure to employ a supporting skeleton on steel beams and columns. However, it is dwarfed by today’s tall buildings, and city planners, manufacturers, and architects are working to develop new ways to build higher. Of the world’s 770 buildings taller than 200 m (656 ft), 66 were built in 2012. There are currently 71 buildings standing more than 300 m (984 ft) in height, and two ‘mega-tall’ buildings reaching 600 m (1968 ft). By 2020, eight more mega-talls are expected, as well as the world’s first kilometre-tall building.

Until recently, elevator technology has not been prepared to accommodate these future buildings, and it has been impossible to travel a kilometre upward in a single elevator ride. Even continuous travel of just 500 m (1640 ft)—or about 100 floors—has proved challenging, and in some cases impossible, with existing technology. Historically, the sheer weight of the kilometres of rope needed to hoist the elevator and additional rope needed to lift the cables has been the largest barrier. Buildings have addressed this limitation with ‘sky lobbies,’ in which passengers transfer from one elevator to another to reach their desired floor.

The barrier to continuous elevator travel in the world’s tallest buildings has stumped elevator manufacturers for years. Now, a revolutionary technology—the result of a fresh approach to elevator hoisting—is reinventing the high-rise elevator and turning these limitations upside down.

A new way

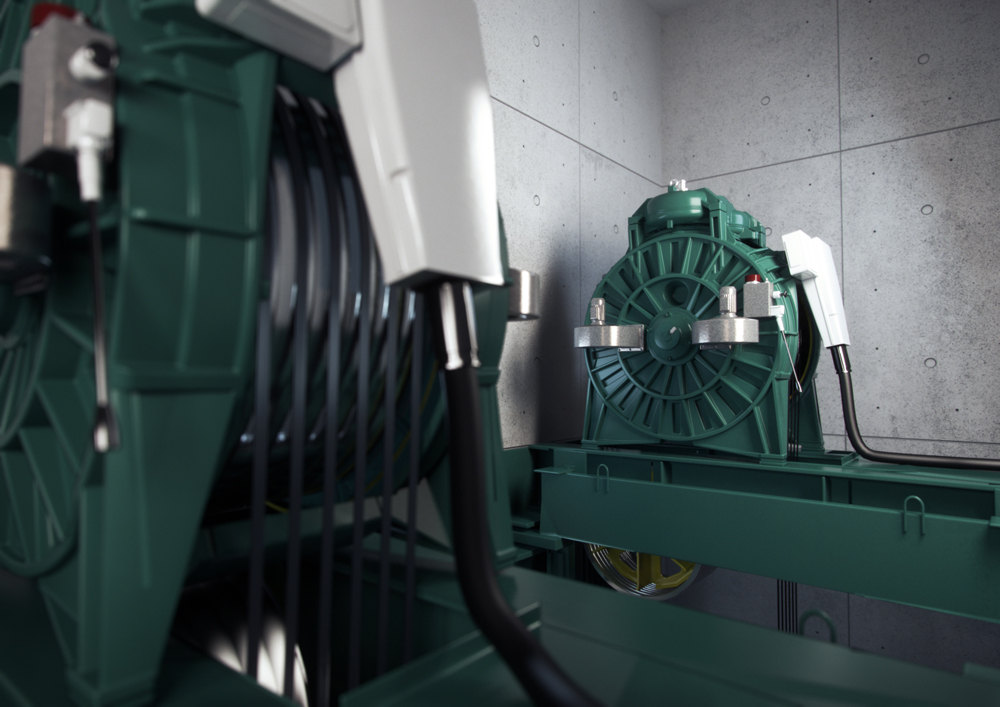

Last year, a new super-light hoisting technology was released to the market, establishing a benchmark for high-rise buildings by eliminating the disadvantages of traditional steel ropes. Using light and durable carbon fibre, this method greatly overcomes the limitations of existing technologies, such as high energy consumption, rope stretch, large moving masses, and downtime caused by building sway. Not only do the rope’s features address the practical needs of the world’s tallest buildings, but they also anticipate the growing need to conserve energy in highly-populated areas. This carbon-fiber technology may be applied to skyscrapers of all heights. However, the benefits are most noticeable in the largest skyscrapers.

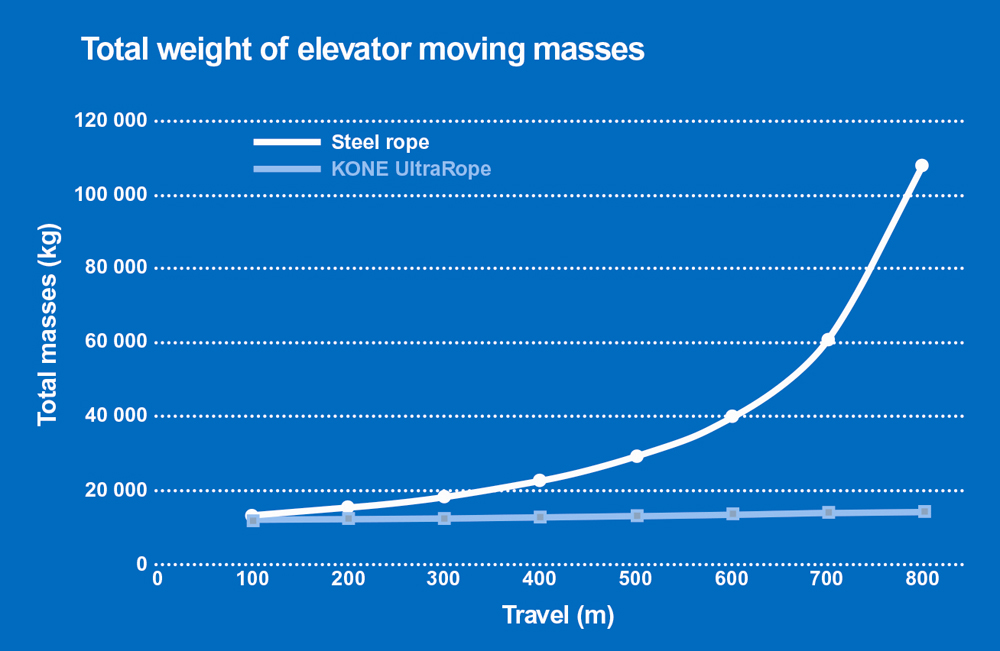

Weighing in at just 19 per cent of a similar-strength conventional steel cable, the rope’s lightness plays a critical role in reducing elevator energy consumption. Lighter ropes require lighter counterweights and slings, further reducing the weight of moving masses, the deadweight travelling up and down with an elevator. For example, the moving masses of a single elevator hoisted with a steel rope in a 500-m tall building can weigh up to 27,000 kg (59,525 lb). Using the new technology in a similar shaft, moving masses weigh only 13,000 kg (28,660 lb)—a reduction in weight of more than 50 per cent. This reduction corresponds to lower energy consumption and operating costs, which increase exponentially as travel distance grows. For example, while energy savings for a 500-m elevator journey are around 15 per cent compared to a conventional steel rope, savings are more than 40 per cent for an 800-m (2624-ft) journey.

Additionally, the ropes are incredibly strong, and resistant to rust, stretch, and wear. The need to be changed at regular intervals—a huge challenge in tall buildings—is greatly reduced due to the technology’s long lifetime—twice that of a conventional steel rope. Additionally, the use of high-friction coating eliminates the need for lubrication, and enables further reductions to environmental impact.

Finally, the materials in the rope resonate at a completely different frequency than steel and most building materials. As a result, the ropes are less sensitive to building sway, greatly reducing elevator downtime costs as a result of strong winds and storms.

Finally, the materials in the rope resonate at a completely different frequency than steel and most building materials. As a result, the ropes are less sensitive to building sway, greatly reducing elevator downtime costs as a result of strong winds and storms.

These advances in efficiency, durability, and reliability provide unprecedented opportunities for high-rise buildings by enabling future elevator travel heights of up to 1000 m (3281 ft)—twice as high as what is possible today. Breaking the limitations of traditional heavy elevator cables, this new technology will allow buildings to soar higher.

Looking forward

Currently, this technology is not found in North America. However, Marina Bay Sands, a recently opened 200-m (656-ft) tall resort in Singapore employs the carbon-fibre technology. Denser concentrations of people in urban environments will increase the importance of efficient movement in and between buildings. With greater people flow, buildings will be built higher and greater efficiency will become essential. Urbanization is a guiding trend for the construction industry. While it may not be intuitive, elevators enable the vertical growth of cities, and they will continue to play a critical role in facilitating the sky-high buildings of the future.

Notes

1 For more, see A Briefing on Climate Change and Cities at www.britishcouncil.org/science-briefing-sheet-30-climate-and-cities-dec04.doc.

Kellie Lindquist is a LEED Green Associate and marketing manager with KONE Americas, as well as a member of KONE’s Environmental Excellence Strategy Team. She is an experienced writer and public speaker on topics including how vertical transportation can be selected to reduce overall building energy use, along with the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program. She can be contacted at kellie.lindquist@kone.com.