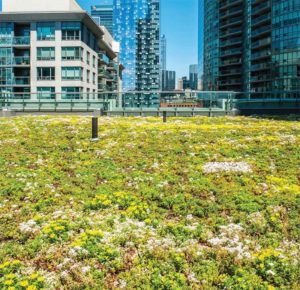

Reinventing the traditional vegetated roof for detention

By Sasha Aguilera, B.Arch, GRP, and Brad Garner

Vegetated roofs, more commonly known as green or live roofs, are a sustainable solution emulating and echoing designs found in nature in response to modern human challenges. This nature-inspired innovation is known as biomimicry (read Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature by Janine Benyus, published in 1997 by Harper Collins).

One early example of biomimicry was Leonardo da Vinci’s study of the bird’s anatomy to enable human flight. Today, researchers continue to study nature to develop new technologies, such as the bullet train modelled after the kingfisher bird to reduce noise and increase speed and efficiency. The most ubiquitous example of biomimicry is the removable, re-useable, all-surface fastener inspired by the tiny hooks on bur fruits (refer to Sustainability: Essentials for Business by Scott T. Young and Kanwalroop Kathy Dhanda, published in 2013 by Sage Publications Inc).

As climate change presents an increased risk to urban stormwater management (SWM), watersheds, and public health overall, implementing green infrastructure has become a key tool to help manage rainwater where it falls, and thus increase community resiliency (consult “Report on the Environmental Benefits and Costs of Green Roof Technology” by D. Banting, H. Doshi, J. Li, and P. Missious for the City of Toronto).

Modern vegetated roofs bring nature back to the cities for a plethora of benefits, using available space on rooftops, mostly for SWM benefit.

Traditional vegetated roofs achieve retention by holding a certain amount of rainfall onsite. After they are fully saturated and retention is maximized, additional rainfall drains through as quickly as it falls. Detention technology takes over where retention capacity ends. Detention helps manage the excess rainfall onsite by slowly releasing it to prepare for the next event, within a matter of hours or days. Now, a detention layer in vegetated roof systems helps manage the excess stormwater runoff onsite by mimicking friction found in watersheds and aquifers. Friction in nature includes tall grasses in meadows, dense masses of reeds in wetlands, or layers of leaves on a forest floor. Friction-detention in vegetated roofs is a technological innovation inspired by nature to achieve rooftop SWM in dense urban areas.

Traditional vegetated roof systems

There are many types of vegetated roofs, and generally fall under two classifications: intensive or extensive. Intensive roofs feature a variety of plants in a heavy and deep substrate layer of 250 mm (10 in.) or more. Extensive roof systems, on the other hand, are lighter in weight because of a shallow substrate of 20 to 150 mm (3⁄4 to 6 in.) and they typically feature vigorous, low-growing, drought-tolerant plant species such as sedums and mosses. Extensive systems are economical, easier to remove and repair, and require less maintenance than the intensive ones. Extensive systems may also be retrofitted on existing buildings. This article focuses on extensive vegetated systems.

How do vegetated roofs work?

The main principle components of a green roof are explained below.

Vegetation

Most extensive vegetated roofs include succulent plants such as sedums (read “Sedum cools soil and can improve neighboring plant performance during water deficit on a green roof” by C. Butler and C.M. Orians for Ecological Engineering, 2011). Sedums have thick leaves in which they store water, making them more heat- and drought-tolerant and better suited for rooftop survival (read “Sedum cools soil and can improve neighboring plant performance during water deficit on a green roof” by C. Butler and C.M. Orians for Ecological Engineering, 2011). When it is not raining, the vegetation uses the water stored in the growing medium and the leaves and releases it to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration (explained later). The water that is released to the atmosphere and never becomes runoff is retained water contrary to detained water, which eventually becomes runoff.