The Invisible Threat: Creating bird-friendly buildings

By Christine Sheppard, PhD, Anne Lewis, FAIA, Bruce Fowle, FAIA, and Guy Maxwell, AIA

Ask most facility managers about birds and they probably think about pigeons nesting on air-conditioning units or Canada geese fouling walkways. However, most species also contribute to insect control, habitat-regenerating seed dispersal, as well as spring song and bright colours.

Unfortunately, the increasing use of glass in the built environment has been reflected in an enormous, but little-recognized toll—annually, about 25 million birds are killed by collisions with glass in Canada, and up to one billion in the U.S. As interest grows in this, and other sustainability issues, the building industry is in a unique position to respond.1

Why do birds collide with glass?

Why do birds collide with glass?

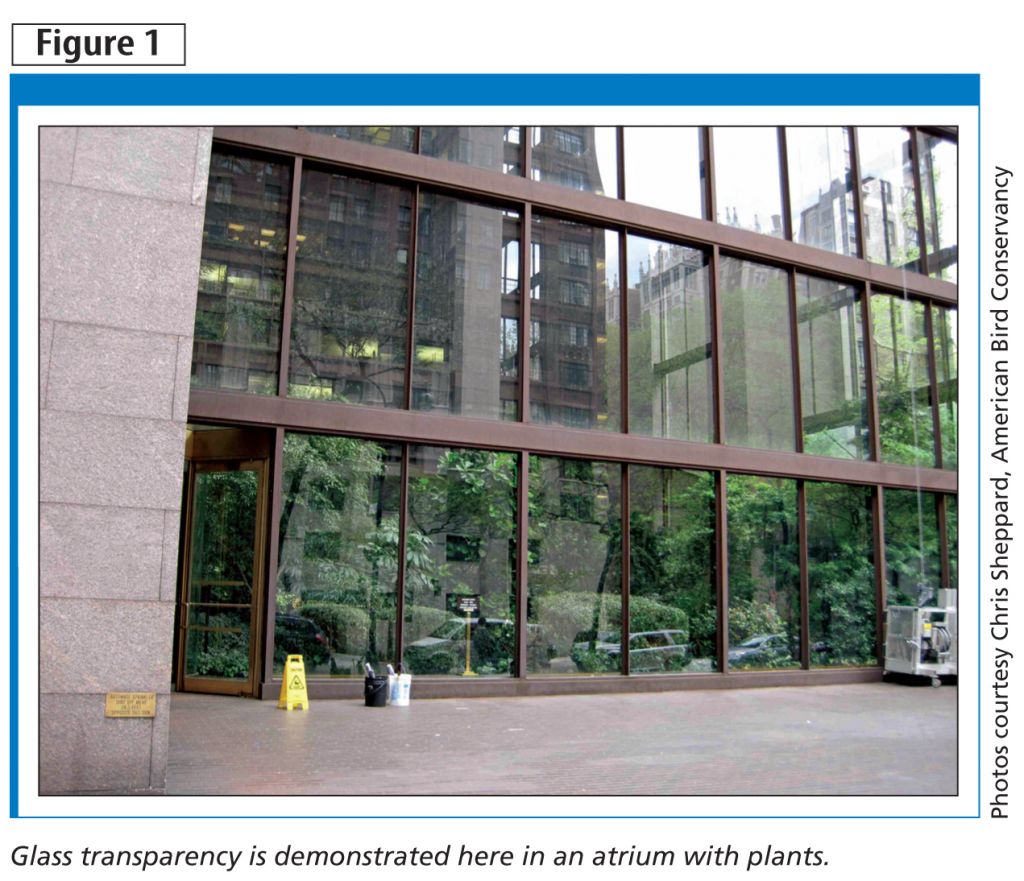

Some wonder why they can see glass and birds cannot. In reality, people cannot see glass either and injuries can occur. However, people come to recognize mullions and window frames mean glass—context that is meaningless to birds. Birds try to fly toward reflected vegetation or sky, or to habitat seen through glass, and because they often fly into small spaces, even minimal glass can pose a hazard. This is why virtually everyone has seen or heard a bird hit a window.

Most collision victims are small songbirds, such as thrushes, warblers, sparrows, and tanagers—some of the most beloved and colourful species. These birds are neotropical migrants, meaning twice a year they travel between wintering grounds in South and Central America in the fall and breeding grounds in Canada in the spring. Most songbirds migrate at night, often travelling up to 124 km (200 mi) daily at speeds of approximately 48 km/h (30 mph). In the early morning hours, they come down to rest and feed, often attracted to urban areas by the glow of city lights. Many collisions occur during these spring and fall migratory seasons because the birds are in unfamiliar territory and do not recognize the glass-clad structures.

Further, bird vision is different than that of humans. The former has four retinal cones, while the latter has only three, and they also perceive more colours and can see ultraviolet (UV) light. Their response time is quicker, and they have excellent peripheral vision because their eyes are on the sides of their head. However, for the same reason, their binocular vision is limited and depth perception is poor. Birds are also less sensitive to contrasts—meaning they need to be closer to resolve two adjacent objects. So, at 48 km/h, they have little time to avoid colliding with glass, even if they see it.

A commonly asked question is, if so many birds are killed by glass, why are more dead birds not seen on the ground? While some are disposed of by maintenance workers, most are taken by scavengers like rats, raccoons, cats, crows, and gulls. Some scavengers actually patrol areas where collision victims are frequently found. It is important to note residential homes likely kill more birds than other types of buildings due to the typical bucolic settings.