Fire and sound control for safety and well-being benefits of better acoustics

By Robert (Bob) Marshall, P.Eng., BDS, LEED AP

For decades, Canadian urban development has been dominated by high-rise condo buildings, large apartment complexes, and single-family dwellings—without much in between. However, as more people move into cities and suburbs, municipal governments are facing increased pressure to contain their sprawling boundaries and provide affordable options as resources are stretched. To address this challenge, developers have increasingly turned to mid and high-rise buildings.

In the past, building codes required these structures be made of concrete and steel, but recent changes to the 2015 National Building Code of Canada (NBC) have permitted the construction of six-storey wooden structures nationwide, with plans to increase the limit to 12 storeys by 2020. With strict safety measures, Vancouver and some other jurisdictions have allowed even taller timber structures, like the 18-storey University of British Columbia (UBC) project, Brock Commons. (For more on this project, see the June 2017 Construction Canada article, “Introducing Brock Commons: Looking Up to the World’s Tallest Contemporary Wood Building,” by John Metras, Ralph Austin, and Karla Fraser. Visit www.constructioncanada.net/introducing-brock-commons-looking-up-to-the-worlds-tallest-contemporary-wood-building.) Indeed, in many ways, Vancouver is the Canadian leader in innovation and codes—the city also requires high levels of energy efficiency, including Passive House. (The photo above shows a six-storey wood mid-rise in Vancouver—one of the country’s largest Passive projects.)

As with all new innovations, this inevitably presents new challenges. In the case of taller wood-framed and timber structures, dealing with not only the risks of fire, but also challenges with sound transmission is essential to the health and well-being of the occupants. Planning at the concept stage and employing smarter designs can help mitigate some of the dangers of fire and/or smoke spread and excessive noise.

Photo courtesy Cedaridge Services Inc.

Fire risks are a complex topic and are currently being considered by incorporating encapsulated cross-laminated timber (CLT) in preparation of the 2020 NBC. (Figure 1 shows gypsum encapsulation of CLT floors.) Generally, this requires a balanced approach, which should include early-warning systems, egress, restrictions on material flammability/combustibility, gypsum-encapsulated wood, steel compartmentation, and sprinklers.

The connection between fire protection and sound control

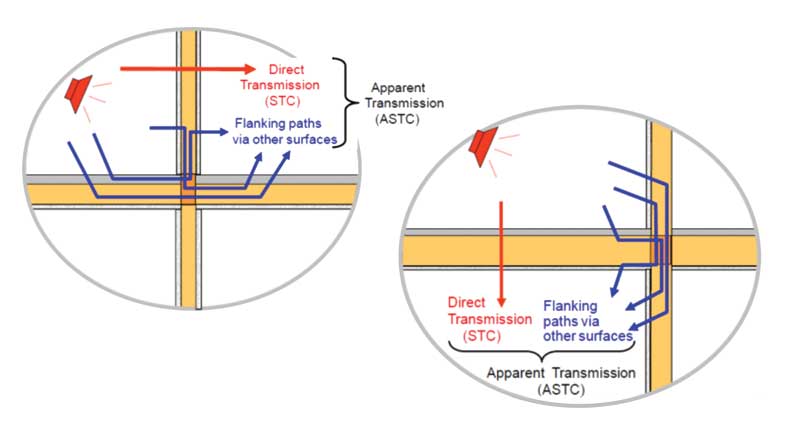

Canadians are living in closer proximity to each other than ever before. As a result, the top complaint from residents of shared buildings is noise. This challenge is often magnified in wood-framed construction where there are multiple wall and floor building connections particularly susceptible to flanking paths (Figure 2).

These flanking paths are where air—and therefore fire, smoke, and noise—can move from one unit to another through the gaps between studs, joists, drywall, ceilings, and other seams. Places where smoke and fire can more easily move through these spaces affects fire spread of the overall structure and the level of ambient noise in the building. This raises safety concerns that must be addressed by designers, authorities, and contractors.

Aside from the obvious threat of fire, a lesser-known health hazard can be found with the issue of noise. High levels of noise have been shown to cause headaches, hypertension, stress, irritability, and high blood pressure. (For more information on acoustic design in healthcare environments, visit www.cisca.org/files/public/Acoustics%20in%20Healthcare%20Environments_CISCA.pdf.) At work, this can lead to decreased productivity, increased sick time, and higher turnover; at home, negative impacts include sleep loss and elevated stress levels, compounding over time.

Image courtesy National Research Council

The significance and potential health hazards of excessive noise have not been lost on regulators. Canada has higher code requirements for acoustics included in the 2015 NBC’s introduction of requirements for apparent sound transmission class rating (ASTC). These requirements raise sound control requirements beyond those of the traditional sound transmission class ratings (STC), which are based on the transfer of sound through walls separating two spaces. Generally speaking, the higher the number, the less sound is transmitted through the wall. These ratings are determined in a laboratory setting under controlled circumstances, which do not always translate into real-world scenarios.

Sound can travel between condo, apartment, hotel, and retirement units through ceiling spaces, demising and corridor walls, and floors. Other potential paths include pipes, electrical outlets, and other flanking paths circumventing STC-rated walls and floors. The ASTC ratings have been developed with these realities in mind; they better reflect how noise moves through these spaces horizontally, vertically, and diagonally. To meet these new requirements, which are in the process of being adopted by jurisdictions across the country, designers should look to third-party-tested assemblies for compliance and in order to reduce risks.