Making a case for sprayfoam in the unvented attic

By Peter Birkbeck, CTR

Unvented attics have been designed and constructed for some 30 years. They are referred to by various names, including conditioned attics, semi-conditioned attics, indirectly conditioned attics, hot roofs, and compact roofs. Across North America, they have been the subject of numerous technical studies, papers, and—in some cases—building code proposals and changes. However, the strategy has rarely received as much attention as it has in recent years.

For the most part, unvented attics are a residential phenomenon. For residential low-sloped roofs, most building codes require attic space ventilation; Canadian building codes typically call for a net free ventilation area of 1:300, or 0.09 m2 (1 sf) in 29 m2 (300 sf) of insulated floor area.

This is increased to 1:150 for roofs of slope less than 1:6. Other provisions in the National Building Code of Canada (NBC) speak to a high-low distribution of venting, as well as a symmetrical provision of roof venting on either ‘side’ of the roof.

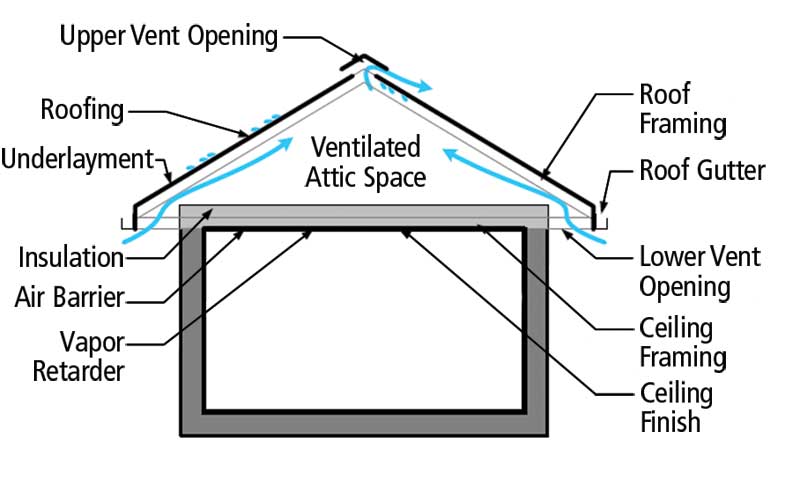

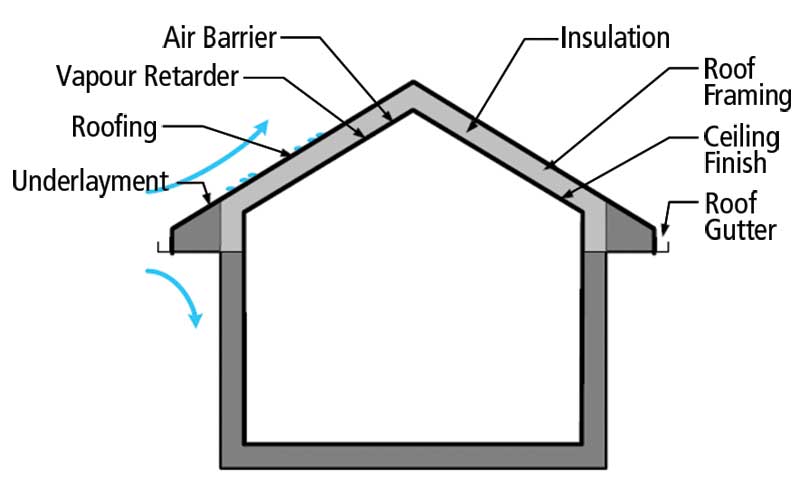

Creating an unvented roof generally involves moving a combination of the thermal, air, and/or vapour control layers to below the roof sheathing without any venting whatsoever. In a traditional design, these layers would be located at the horizontal plane of the ceiling.

In conventional attic construction, two designs are possible. In the first configuration, a sloped roof encloses the entire attic (i.e. roof) space, which is ventilated. Thermal insulation is placed above the uppermost horizontal ceiling finish, and the air and vapour control layers are also located in this plane. Depending on the design and climate, the resulting space may be used to hold mechanical equipment and services (such as space-conditioning equipment and ducting), provide access for repair and maintenance purposes, and possibly allow for storage or future occupancy.

The second option is a cathedralized attic, where all control layers are located at the sloped roof plane, just inside the interior finish. Some designers and owners find this approach more visually pleasing.

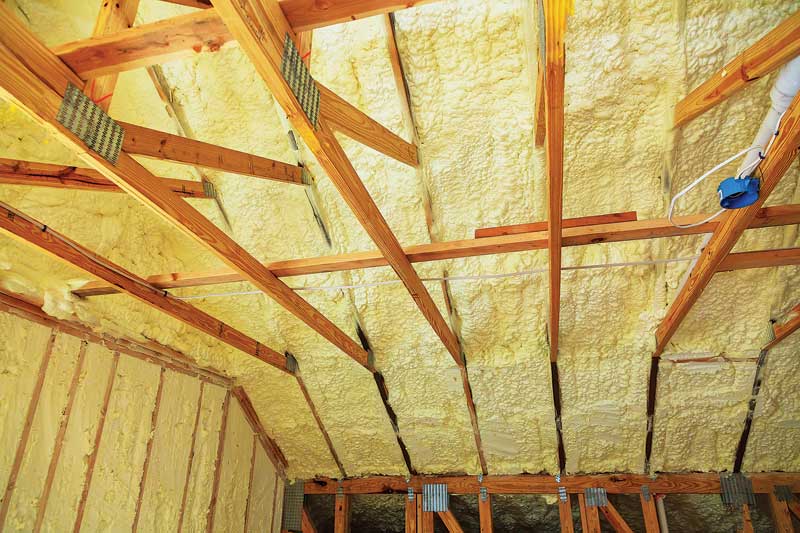

Images courtesy Icynene Inc.

Why construct an unvented roof space?

Other than the practical reasons and visual appeal already mentioned, unvented roof spaces may have additional collateral benefits, such as:

- reducing potential for burning embers to be introduced into the roof space in the event of a forest fire in wildland areas;

- lessening potential for roof uplift from wind gusts in areas prone to high wind (i.e. hurricane) events;

- housing mechanical equipment, ducts, and other services—especially if no such space exists below-grade—which generally results in more energy-efficient operation and allows any duct leakage to be contained within the indirectly

conditioned space; - permitting the easier incorporation of control layers (i.e. thermal, air, and vapour) in complex roof designs (which seem today to be more of the norm than the exception);

- reducing the potential for ‘ice-damming’ by controlling heat loss through the ceiling plane; and

- preventing snow from being blown into the

roof space.