Weatherproofing ICF Walls: Lessons in resiliency from B.C. field testing

By Douglas Bennion

Successful independent field-testing and code compliance analysis in British Columbia has resulted in the compilation of the first comprehensive set of residential construction details for insulating concrete forms (ICFs) in North America. From footings to trusses, the ICF details presented in the provincial Homeowner Protection Office’s (HPO’s) upcoming release, “Building Envelope Guide for Houses,” offer a concise and cost-effective path to best practices and B.C. code compliance. Ongoing efforts indicate a strong potential for expanded adoption of these details in jurisdictions across Canada.

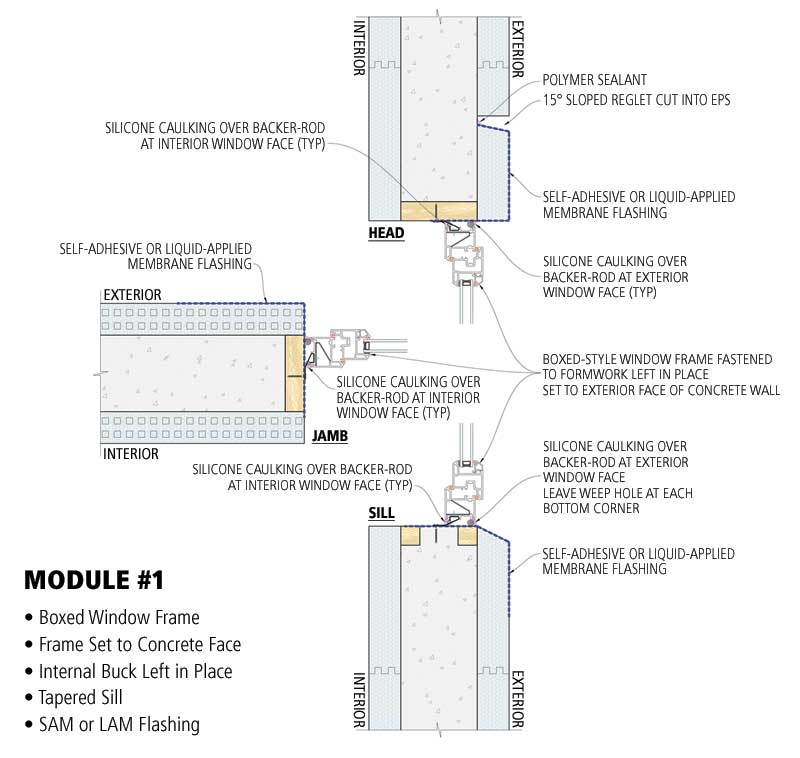

Many different methods—and even more opinions—exist on weatherproofing ICF walls. Only recently has the industry had scientific evidence upon which to base best practices for installation of window and door openings in such walls. “ICF Field Testing Report,” a research report issued by HPO, provides a range of solutions compliant with building codes such as the B.C. Building Code, Part 9 (which is modelled after the 2015 National Building Code of Canada [NBC]). These solutions address the widest-possible range of building types, from single-family homes to high-rise commercial buildings.

To convey the report’s findings and make them easily applicable to individual projects, it is best to start at the core of the issue—how to permanently prevent air and water leakage at window and door openings in ICF walls. The answer begins with the following two basic code-compliant paths to water resistance in building shells.

Images courtesy Quad-Lock Building Systems

Moisture protection plane

Mainly concerned with wood-framed walls, building codes typically call for a primary weather barrier (such as siding or stucco) with a secondary weather barrier (such as building paper or another synthetic membrane) behind it. This is because framed walls must be kept dry to protect against moisture damage to both framing members and the insulation within.

Both codes, however, contain exemptions from the secondary weather barrier requirement in the case of above-grade masonry or concrete walls, which are recognized as watertight planes and shed water adequately on their own. As a result of the research summarized later in this article, ICF walls are now characterized as a complete assembly under B.C. residential code, without the benefit of added building paper or air gap (i.e. rainscreen) behind exterior cladding. This means ICF walls will not be subject to the same requirements for added weather protection as wood-framed walls, but the same exemptions as other concrete and masonry walls, which are recognized as able to resist water penetration on their own, without added layers of protection.

Exterior insulation

The expanded polystyrene (EPS) used in the manufacture of ICFs will not permit the passage of water or water vapour, but the horizontal and vertical joints between ICF units can allow penetration of water driven either by wind or gravity. This is an apparent conflict with building codes, which typically require the exterior building shell to be able to shed water to the outermost plane of the wall, where it cannot harm wood framing. Unable to view concrete behind the ICF outer insulation, building officials often default to more familiar wood-framed construction requirements and expect a membrane between the building sheathing and the exterior cladding. This has not only proven to be unnecessary, but is also unpopular among ICF proponents who object to the added costs.