Polished concrete’s warring state

By Christopher Bennett

After delivering a talk as part of the Architectural Praxis concrete education series at the 2015 CONSTRUCT Show & CSI Annual Convention in St. Louis, this author ran into Keith Robinson, FCSC, RSW, LEED AP, former CSC president and a specifier with DIALOG . He mentioned he and his colleagues had been building their polished concrete specifications since 2004, but with each project, they continued to encounter different outcomes, many times with the same spec.

Robinson said he had been trying to “obtain a forensic opinion on how the appearance can change so remarkably between one project and the next.” Unfortunately for him (and many other specifiers in Canada), polished concrete specifications have become more restrictive and still enjoy very little in the way of consistent results. The restrictive nature of the specifications leaves the architectural firm or their client on the hook for change orders, and all parties involved scratching their heads trying to decide what went wrong and wondering if everyone is even speaking the same language.

Ironically, language around specifying polished concrete was exactly the topic for that CONSTRUCT seminar. More specifically, I offered up the idea our current language for specifying all concrete surfaces is much like the ‘Warring States Period’ of ancient China (475 to 221 BC). Prior to Chinese unification by the ancient kingdom of Qin, there were multiple competing writing systems that made communication very difficult. Today’s specifiers, like China’s first emperor, have to contend with varying, and often contradictory, language in specifying design intent.

One of the first items the Qin emperor tackled was standardization of weights, measures, and language. Can you imagine trying to construct the Great Wall, the Grand Canal, or the Forbidden City with competing systems for writing? It seems absurd and yet this is an appropriate comparison to modern-day construction and specifications language for describing concrete surfaces.

When using terms like “grit” or “gloss” in specifications, does that mean the same thing to every subcontractor bidding the project or is it open to interpretation? It can be very difficult to guarantee clients sustainability and low-maintenance polished concrete flooring with the overabundance of subjective language available to specifiers these days. There is no need to pack up the ox cart and head to Chengdu just yet, though—we are far from imminent collapse and invasion from beyond the Wall. Sustainable, beautiful, and easily maintainable floors are quite possible if one learns the right language. This article looks at some of the definitions and terms already in use, as well as some new methods for describing design intent with concrete finishes to help make some sense of it all.

Map courtesy of Gabriele Roncoroni

Specifying reflectivity and refinement: What is ‘shiny?’

There are a number of ‘dictionaries’ available on how to make concrete ‘shiny.’ Some of these definitions provide recipes that create sustainable floors, but most do not. To make matters worse, they almost always seem to be sold and described as ‘polished,’ regardless if any actually polishing takes place. There are both manufacturers and trade organizations that describe ‘types’ or ‘degrees’ of polishing as ‘scrubbing’ or ‘sealing,’ but do those terms accurately define polished concrete?

The word polish is defined as “becoming smooth and shiny by rubbing.” The modern Chinese word for polish comprises two characters—“mo” and “guang.” The first character depicts the action of rubbing with a stone, while the second means ‘bright.’ In either English or Chinese, polishing describes a process of physical refinement. Yet the hordes of guards, grouts, sealers, and coatings from MasterFormat Division 09 (Finishes) continue to invade the best intentions of Division 03 (Concrete).

“Many Canadian specifiers rely on simple language and take their chances with outcomes,” Robinson later explained. “When I looked for content in my local specifier share group, no one had examples of successful grinding and polishing specifications. Largely, we rely on including photographic references and addresses to projects that were found to be acceptable—a qualitative example, but unfortunately not quantifiable when things don’t go as expected.”

Finding the right language can be difficult. Many polishing lexicons offer an alphanumeric range of polish levels in an effort to make specifying easier, but in looking closely at the definitions of these individual levels, we discover these ‘set levels’ are not easy to measure. There is existing language defining certain levels of reflectivity to be sharp or crisp. Is it even possible to quantify crispness? The ancient Chinese invented gunpowder and the compass, but there is no mention of a ‘crisp-o-meter’ in the Records of the Grand Historian.

Other definitions of reflectivity will include language like ‘slight diffusion.’ However, what is slightly diffused to some may not be slightly diffused to others. Is a change order necessary because one party believes there is not yet enough slight diffusion in the floor or is it instead that slight diffusion has, in fact, been reached, but nobody can tell? Can the contractor get paid yet? Is my client’s floor actually polished? It seems we are again trying to communicate design intent with language inherently subjective and open to interpretation.

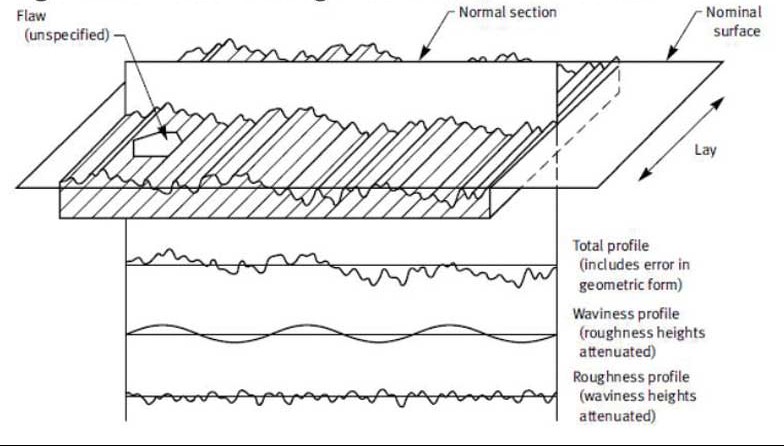

Image courtesy Concrete Sawing & Drilling Association

Shedding some light on meters

The industry has attempted to quantify reflectivity with light meters. There are still many specifications from manufacturers and architects that attempt to describe design intent by requiring a certain amount of radiant light be reflected off the surface of the floor, and then measuring that reflected light on substantial completion of the floor.

The devices used to carry out these tasks are called gloss meters, with the degrees of radiant light measured in lumens (lm). These tools are useful for various applications and are extremely accurate for reporting the amount of gloss reflected off the floor, but they do not begin to tell you why that light is being reflected. Was your concrete properly refined and polished (i.e. is it durable and sustainable?) or did a product from Division 09 ride down from the North and invade your client’s slab again?

Robinson had this to say about gloss meters and sealers

“We have attempted to describe gloss levels, but measuring has been pretty much impossible and enforcing any of the referenced standards—ASTM C346, C584, and D523—has been trying,” he explained. (The standards in question are ASTM C346, Standard Test Method for 45-deg Specular Gloss of Ceramic Materials, ASTM C584, Standard Test Method for Specular Gloss of Glazed Ceramic Whitewares and Related Products, and ASTM D523, Standard Test Method for Specular Gloss). “Concrete ‘doping’ has done a disservice to the industry as a whole by trying to market into so many niche categories. It is my honest opinion that very few people could tell the difference [between sealers and physically refined polished floors] and when a contractor has pulled an apparent substitution, we cannot tell the difference until the floor performance is affected.”