Beware Of Falling Ice And Snow: A winter perspective on building design

By Mike Carter, CET, and Roman Stangl, CET

On a cold February morning, as people walk to their new downtown office buildings (in Toronto, Montréal, Winnipeg, Calgary, or Ottawa), a loud crash is heard, sending them scattering outside the main entrance. Ice shards rain down onto the sidewalk, with a large ice chunk smashing the ground directly in front of the main doors. This is not a Hollywood disaster movie blockbuster, but an actual, all-too-often occurrence.

Design and construction practices are changing in many ways—trends toward energy conservation, unique architecture, taller buildings, and use of advanced technologies and materials—and are having an impact on the performance of a building within its environment. Granted, many projects go through significant scrutiny before being commissioned, but the issue of falling ice and snow is seemingly not in the forefront.

Understanding how the completed building performs under the adverse conditions of a winter storm event seems to be absent from the current design process, or at least low on the priority list. Façades of high-rises are commonly tested during the design stage to investigate their performance for water penetration, air infiltration, thermal performance, and structural capabilities. However, only a few are ever tested for ice and snow collection and release. Consequently, the reported incidents of falling ice and snow in urban areas is increasing throughout North America.

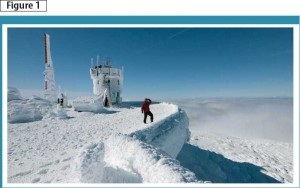

Photo courtesy Mount Washington Observatory

Rise of falling snow consulting

The history of consulting and investigating in this field started with some well-meaning engineers and technical folks who were approached with reports of ice and snow falling from buildings and thought to themselves, “We can fix that.” Experience was gained over time as reputations grew and successful solutions were implemented. Soon, clients came with more challenging questions, such as, “Can you look at my drawings and tell me how to avoid problems in the future?” or, “How small can we make the solution?” These tasks required investigation and research.

This involved quantifying the effectiveness of various mitigation options or design modifications, along with physical testing in cold-room research laboratories or at outdoor venues like Mount Washington Observatory in New Hampshire (Figure 1). There is, needless to say, much dedication required for those who choose to be responsible for conducting and observing a high elevation icing test, intended to replicate the top of a super-tall structure somewhere else in the world, by standing atop the observatory lookout in freezing cold temperatures, with the clouds rushing by below you. Mount Washington, after all, is where a wind gust of 372 km/h (231 mph) was measured in April 1934—the highest wind speed ever observed.

Photos courtesy Northern Microclimate Inc.

The gathering of this type of knowledge and experience has led to some interesting realizations regarding industry trends and the need for education within the building profession. First, on review of numerous building designs and incident reports, it is evident the design industry is not properly informed regarding ice and snow on building details. This is particularly the case for sloped roof surfaces, whether they are asphalt, slate, metal, or membrane. The occurrence of ice dams causing leakage, sliding snow causing damage (Figure 2), or the generation of dangerous icicles that fall from roof edges is common (Figure 3).

The realization the design industry as a whole has very little guidance from building codes or standards and little in the form of formal education to address ice and snow on buildings, outside of static structural loads, was surprising. The attitude of some designers is the responsibility for dealing with snow and ice belongs to the structural engineer. Consequently, as ice and snow consultants, this article’s authors find the first task is often the education of the design team regarding the typical microclimate conditions that will exist on their proposed building in the winter months.

In short, we strive to put a picture in the minds of the architects of their proposed building on February 22, rather than August 1 (most of the beautiful project renderings on drawing set covers tend to be in the summer). This education is done through descriptions of typical winter storm events and photographs of buildings with the resultant problematic snow and ice formations. This insight often creates expressions of concern or just utter silence in the meeting room. “That won’t happen on my building…will it?” The answer tends to be, “Yes, it is possible”.

Technological impacts

A second realization about the design industry is regarding the very positive and progressive trends of advanced technologies and energy conservation. In the days before energy conservation, buildings were constructed as large simple boxes that leaked heat from every façade and surface. Single-pane glazing, double-brick walls, and badly insulated attics created relatively warm exterior surfaces, which would melt ice and snow on contact (or soon after).

One might think Canada’s extreme cold periods would cause a building’s outside skin to dip below freezing. While this does occur, the largest and most problematic ice and snow storms tend to happen when air temperatures are just below or above freezing. Therefore, a majority of the time snow and ice occur, they just melt off the building.

In these modern times of extreme insulation, double- and triple-pane glazing, and very efficient internal heating strategies, the outside skins of buildings are much colder. To further complicate matters, the industry no longer constructs simple boxes. The built environment has progressed to unique curves, slopes, and shapes that gather more snow than would a simple vertical wall topped by a tall parapet at the edge of a flat roof. Adding insult to potential injury, heat-reduction strategies (e.g. solar shading devices) are often specified for the skin’s exterior, with little thought to the implications. The result is Canadian buildings that are in effect ice generators. The accumulated snow can age and harden into ice and icicles that fall great distances to the building’s base, thanks to the influence of wind (Figure 4).

Technology has allowed us to build bigger, taller buildings than ever before. This has led to structures that literally have their heads in the clouds, where it is cold and wet (i.e. ice and snow). This technology has also resulted in large stadiums, arenas, and shopping malls with big curved or sloped roofs where large volumes of ice and snow can slide or be wind-drifted into snow dunes.

Modern design has allowed for unique building shapes with hills, valleys, troughs, and snow shoots. As initially stated, technology and energy efficiency are positive trends, but they are also creating some unintended hazards that are relatively simple to deal with if they can be appropriately identified and addressed.

The renovation or retrofitting of existing buildings with additional insulation can also be problematic, when it comes to ice and snow. This added insulation changes the façade’s performance and, in some cases, leads to hazardous ice and snow conditions in areas that have otherwise done well for many years.

The investigation process

The reality is we have learned from others’ mistakes, as well as from physical testing of proposed façades, and from constantly progressing the experience and science behind falling ice and snow. Thus, as awareness grows around the topic, it is the authors’ hope more designers will be willing to investigate performance.