As the pandemic fades into the past, it has become clear that the relationship with workspaces has been permanently altered.

The ongoing debate over remote work, hybrid models, and a return to traditional offices has revealed an undeniable truth—future work environments will never look the same.

This shift has left a significant mark on cities. According to the Avison Young First Quarter 2022 Office Market Report, the downtown office vacancy rate in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) surged to eight per cent, up from just 2.1 per cent the previous year.

Even long-standing tenants are rethinking the future of their buildings, exploring new possibilities for under-utilized office spaces. With an increasing number of vacant office spaces and the demand for housing intensifying, the question arises: What should be done with these empty spaces?

Adaptive reuse, the process of transforming existing buildings for new purposes, presents a compelling solution. However, whether it can effectively address the housing crisis and environmental challenges remains to be seen.

The potential for adaptive reuse is immense, yet the path forward is anything but simple. As this evolving landscape is navigated, its significance and complexities require full attention and innovative thinking.

Renewed emphasis on adaptive reuse

Adaptive reuse has long been a familiar concept in the construction industry but has not always been at the forefront of design strategies.

The practice of transforming old, often neglected buildings into new spaces with entirely different purposes has existed for decades, yet it has only recently gained the spotlight it deserves.

The pandemic, coupled with the urgent call to combat climate change, has renewed emphasis on adaptive reuse as a critical approach in urban development.

In Toronto, several adaptive reuse projects illustrate the potential of this practice. The Evergreen Brickworks, once an abandoned industrial site, has been transformed into a vibrant community hub focused on sustainability and urban ecology.

Similarly, the Toy Factory Lofts repurposed a former factory into modern residential spaces, preserving the building’s industrial character while meeting contemporary living needs.

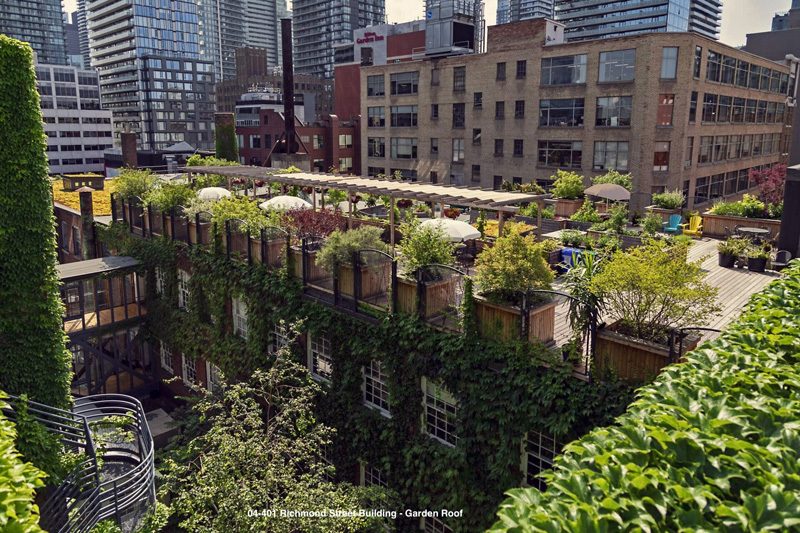

The 401 Richmond Building is another prime example of an old factory converted into a dynamic arts and cultural centre, retaining its historical charm while serving new functions.

These examples highlight adaptive reuse’s esthetic and functional benefits and environmental significance. Repurposing existing structures allows for a substantial reduction in the carbon footprint typically associated with new construction. This is especially crucial in light of the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, which described climate change as “widespread, rapid, and intensifying.”

The urgency of the situation cannot be overstated, and adaptive reuse offers a practical solution to minimize environmental impact by converting old buildings into sustainable, energy-efficient spaces.

Architect Carl Elefante’s assertion that “the greenest building is the one that already exists” holds renewed significance in the current context. What was once merely a nod to sustainability now stands as a guiding principle for shaping urban development in the era of climate change.

Adaptive reuse preserves the past while aligning with the environmental goals of the future, positioning it as an essential strategy in the pursuit of more sustainable cities.

Adaptive reuse example: Office to housing building

In the wake of the pandemic, transforming vacant office buildings into housing seems like a logical solution to the ongoing housing crisis. With affordable housing in short supply, repurposing office spaces could offer a quick fix. However, as straightforward as this idea may sound, the reality of adaptive reuse is far more complex.

The concept of using existing buildings as a cornerstone of sustainability is not new. The assertion “the greenest building is the one that’s already standing,” and reusing structures can significantly reduce carbon emissions—up to 40 per cent, according to British Land’s Sustainable Development report.

So, why not start by converting those empty office buildings? This approach seems like a win-win: addressing the housing shortage while reducing the environmental footprint.

However, the journey from office space to livable housing is fraught with challenges. Scale is a crucial factor in adaptive reuse. While reusing a building shell can have positive environmental impacts, other elements, such as outdated interior materials, may not meet modern standards and could hinder the project.

Adaptive reuse is not just about repurposing a single building; it is about considering a range of scales—from furniture and equipment (product level) to entire cities. At its best, this approach is comprehensive, meeting environmental and community needs.

However, the “best” scenario is rare. Office buildings and residential spaces are fundamentally different. Many older office buildings lack the necessary infrastructure for living spaces: insufficient bathrooms, inadequate natural light, windows that do not open, and ceiling heights that complicate retrofitting HVAC and electrical systems.

According to a CNN article,2 only three per cent of New York City’s office buildings and two per cent in downtown Denver are suitable for residential conversion. The statistics are similar to those of other U.S. and Canadian cities like Toronto.

The evolution of building design also plays a role. In the mid-20th century, before air conditioning became widespread, office buildings were designed with numerous windows to allow for natural ventilation. These buildings typically had smaller floor plates, ranging from 465 to 1,394 m2 (5,000 to 15,000 sf), making them more adaptable for residential use.

In contrast, modern office buildings have larger floor plates—sometimes up to 3,716 m2 (40,000 sf)—making it difficult to convert them into apartments with sufficient natural light and ventilation.

Despite these hurdles, turning empty office spaces into housing remains an optimistic and necessary venture. This effort demands creativity, innovative design solutions, and, above all, a willingness to rethink the use of the built environment.

The challenges are significant, but with the right strategies, this approach could be a key to solving both the housing and environmental crises.

Financial challenges of adaptive reuse

Adaptive reuse sounds like an ideal solution for developers looking to go green—taking an old building and giving it new life demonstrates sustainability. However, once the financial realities hit, the dream often starts to unravel.

Old buildings come with baggage: asbestos, outdated plumbing, creaky structures, and defunct electrical systems. The cost to bring these elements up to code can quickly overwhelm even the most optimistic developer.

Despite these challenges, the appeal of adaptive reuse is undeniable. The buildings are already integrated into their neighbourhoods, offering a blend of character and context that new constructions often lack. Moreover, the environmental benefits are significant—reusing structures minimizes waste, conserves resources, and supports global sustainability objectives.

However, does it make financial sense? The short answer is not immediate. One of the toughest parts of tackling adaptive reuse projects is the uncertainty of when—or even if—these investments will pay off.

Converting under-utilized office spaces into residential units, for instance, presents a major financial challenge. The cost of conversion, paired with the need for competitive pricing in a tight rental market, means developers could be looking at a long wait before seeing any return on their investment.

The median asking rent for apartments is significantly lower than the office rent. The significant price drop in converting office space into residential units makes the math tricky. High vacancy rates further complicate matters, as developers are unlikely to convert a building still performing well as an office.

However, change is on the horizon. Government-backed incentives have been introduced to ease the financial burden of these conversions. Tax policies are evolving, making it more feasible for developers to consider adaptive reuse a viable option.

Adaptive reuse remains a financially challenging project, but with the right incentives and a long-term view, it could become an increasingly attractive option for developers looking to balance sustainability with profitability.

The greenest building practice in the face of climate change

When it comes to combating climate change, the greenest buildings already exist. In Canada, many existing buildings have reached the 50-year mark, presenting a unique opportunity for adaptive reuse.

By preserving, retrofitting, and reusing older structures, significant reductions in the nation’s annual emissions from building operations can be achieved. This approach is not only environmentally responsible but also economically sound.

One of the most compelling reasons to prioritize adaptive reuse is its impact on embodied carbon emissions. Embodied carbon refers to the carbon released during manufacturing, transporting, and assembly of building materials.

Constructing new buildings from scratch releases vast emissions while reusing existing structures avoids 50 to 75 per cent of the embodied carbon a new building would generate. It has to do with renovations typically retaining the most carbon-intensive parts of the building—such as the foundation, structure, and envelope—thereby reducing the overall carbon footprint.

The benefits of reducing embodied carbon through adaptive reuse are immense. Not only does it help achieve emission reduction goals, but it also offers an innovative strategy that can be replicated globally. Shifting the focus from new construction to preserving and retrofitting existing buildings represents a meaningful step toward a more sustainable future.

However, the current rate of building demolition poses a significant challenge to this strategy. According to an article by the American Institute of Architects (AIA),1 approximately 92,903,040 m2 (1 billion sf) of buildings are demolished each year, often for reasons unrelated to the structural integrity of the buildings themselves. In fact,

34 per cent of these demolitions are driven by land-use concepts rather than the physical state of the buildings.

The waste generated from these demolitions is staggering—544.3 million tonnes (600 million tons) of construction and demolition debris were produced in 2018 alone, with demolition waste accounting for more than 90 per cent of this total. Most of this waste ends up in landfills, contributing to air pollution and occupying land that could otherwise be used for farming or forestry.

Adaptive reuse offers a way to mitigate this waste by extending the life of existing buildings. However, it does not stop at embodied carbon. Retrofitting older buildings also dramatically reduces operational carbon emissions—those released during heating, cooling, lighting, and other daily activities within a building.

Improving the energy efficiency of these structures can significantly reduce the operational carbon emitted into the atmosphere.

In urban environments, reusing buildings has the potential to achieve half of the carbon reduction targets necessary to meet global climate goals. Additionally, the economic advantages of retrofitting existing structures are considerable.

Historic rehabilitation projects, for example, have a proven track record of creating jobs and generating private investment. Studies show residential rehabilitation creates more jobs than new construction, making it a win-win for the economy and the environment.

Federal incentives could further bolster the case for adaptive reuse. These credits support rehabilitating historic buildings, making it financially viable for developers to invest in energy-efficient upgrades.

Aligning financial incentives with environmental goals can drive the more widespread adoption of adaptive reuse practices.

Adaptive reuse is more than a viable option—it is necessary to address the challenges of climate change. Prioritizing the preservation and retrofitting of existing building stock enables reducing carbon emissions, conserving resources, and creating a more sustainable built environment. This approach not only aligns with environmental responsibilities but also supports economic interests, presenting a path forward that is both promising and essential.

Key takeaways for architects, developers, and engineers

By focusing on following specific strategies, architects, developers, and engineers can effectively turn adaptive reuse challenges into opportunities for sustainable and successful projects.

- Long-term financial planning: Adaptive reuse requires a long-term perspective. While upgrading old buildings has high initial costs, government incentives and future returns make it a financially viable strategy.

- Maximize sustainability by reusing existing structures: Reusing buildings significantly reduces embodied carbon emissions. Architects should focus on maintaining key structural elements to maximize environmental benefits.

- Address conversion challenges with innovation: Converting office spaces into residential or other uses presents challenges like insufficient natural light and outdated systems. Architects and engineers must develop creative solutions to adapt these spaces effectively.

- Consider the scale of reuse: Adaptive reuse can be applied at different scales, from small interior projects to large urban transformations. Understanding the project’s scale is crucial for planning and impact.

- Enhance energy efficiency: Retrofitting buildings to improve energy efficiency is essential for reducing operational carbon emissions. Utilizing government incentives(s) can help offset these costs.

- Leverage policy support: Government policies and incentives are key to making adaptive reuse viable. Developers should stay informed and advocate for policies that support sustainable practices.

Conclusion

Adaptive reuse has transitioned from being seen as a creative solution to an essential strategy for addressing the critical challenges of the present era.

As cities contend with the dual crises of climate change and post-pandemic reconfiguration, repurposing existing buildings offers a pathway that integrates environmental responsibility with practical urban development.

The transformation of vacant office spaces into housing or other functional uses is not solely a response to economic shifts—it is a crucial measure for reducing the carbon footprint within urban environments.

Reusing structures preserves the embodied carbon invested in these buildings while reducing operational carbon emissions, aligning with broader sustainability objectives.

However, the journey is not without its hurdles. Financial challenges, structural limitations, and regulatory barriers complicate the process, making it clear that adaptive reuse requires long-term planning, innovative design, and strong policy support.

Yet, as seen in projects like Toronto’s Evergreen Brickworks and the 401 Richmond Building, the potential rewards for cities’ environments and vibrancy are immense.

Ultimately, the wisdom that “the greenest building is the one that already exists” rings more accurate than ever. Adaptive reuse offers a way to honour the past while planning a more sustainable future.

It is about reimagining buildings that have served in one capacity to meet the needs of today and tomorrow. Creativity, commitment, and collaboration across the construction industry can turn these challenges into opportunities, building a resilient and sustainable world from existing structures.

Notes

1 Learn more by visiting cnn.com/2024/01/13/business/can-we-turn-empty-office-building-into-housing/index.html

2 Read the article here aia.org/design-excellence/aia-framework-for-design-excellence/resources

Author

Onah Jung, OAA, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, is a seasoned design principal (Studio Jonah) with more than 20 years of experience leading architectural projects across Canada and the United States. With a focus on innovative and sustainable design, she has successfully transformed existing buildings into functional, environmentally conscious spaces. Licensed in Ontario and New York, she holds LEED AP credentials and is dedicated to thoughtful, impactful design.