By Odile Hénault

Tucked in the woods of Saint-Calixte—an hour away from Montréal—is a residential retreat that might have gone unnoticed were its designer not trying to change the way we build and heat our homes. It is an unpretentious statement, advocating better ways of building with wood and simple but efficient harnessing of the sun’s energy. At its own modest scale, this home is becoming one of several projects that will hopefully help the traditional wood industry embark on the 21st century.

Québec architect Dominique Laroche purchased a site that was a short distance from the city, yet immersed in nature. He had long wanted to experiment with passive solar energy and with a relatively new building technique—cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels.

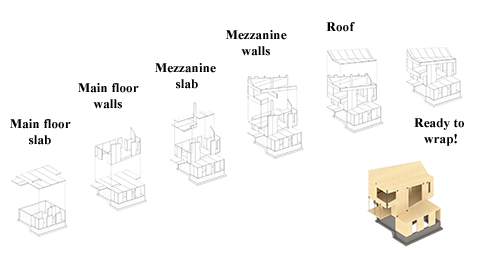

Despite the half-hectare (1.5-acre) property, he wanted a minimal footprint on the ground, in keeping with his ecological beliefs. The design program was straightforward:

- entry level with an open living, dining, and kitchen area;

- partly cantilevered mezzanine level, with the larger portion used as an office and the smaller space as a reading nook; and

- an additional level below with basic sleeping, bathroom, and multifunctional spaces, along with a mechanical room.

The 114-m2 (1225-sf) house is on a steep site, with its lowest level invisible from the road. It is oriented due south—a perfect setting for a passive solar system. The presence of a deciduous forest was a bonus; it would serve as an indispensable condition for the passive solar setup to work adequately, year round.

The promise of CLT panels

Cross-laminated timber panels could be compared to giant sheets of plywood made of solid lumber. Multiple layers (which can vary in depth) are stacked perpendicular to each other, glued and pressed together to make panels that are then machine-cut to size very precisely. Stable and fire-resistant, the panels can be used as walls, floors, and ceilings.

For numerous reasons (including financial ones), Laroche chose to order his CLT panels from the initial manufacturer based in Austria. Although the technology is now fairly widespread in Europe, at the time Laroche designed his project, CLT panels were barely used in Québec, particularly in the single-family housing market.

One of the most convincing demonstration projects had been built by the Austrian company’s Eastern Canada distributors, which had chosen to expand its headquarters in Longueuil, Que. It had commissioned award-winning Montréal architectural firm Daoust Lestage to design their two-level addition as a showcase for CLT panels. The resulting building was warm, airy, and far removed from the usual industrial structure. It showed both the technical and esthetic promises linked to using cross-laminated timber technology.

The main markets targeted by the industry are the medium size commercial, multi-residential, and institutional buildings, where cost benefits due to its numerous advantages—particularly faster assembly time and overall better thermal performance—are quite obvious. For Laroche, however, there was an added motivation in using the prefabricated panels—it was the possibility of developing relatively complex geometrical shapes without having to produce as many working details as would have been required within a more traditional framework. Communicating a project to a CLT panel manufacturer is simply done through 3-D modelling; panels can then be cut to size to 3.2-mm (1/8-in.) accuracy.