Lessons learned in masonry

By David Sovinski

Specifiers, architects, engineers, contractors, installers, and craftworkers all have something valuable to offer to the conversation when it comes to creating high-performing building enclosures.

While people have to be sensitive to contractual relationships, they should also strive to create an environment that encourages open dialogue between all parties. For example, although a masonry installer may have a contractual relationship with a construction manager, there is great value in communication between the subcontractor and architect to discuss expectations, concerns, and creative alternatives based on field experience. Of course, any changes to the scope of work, construction process, or other significant issues should work through the contractual relationship, but a project may suffer without informal conversations.

The International Masonry Institute (IMI) provides services to contractors, designers, owners, and craftworkers through apprenticeship and training, marketing, technical services, continuing education, and research/development. Its masonry hotline connects designers and builders with the nearest service office in North America. The team of technical experts can discuss everything from performance and material section to design options and lifecycle cost. Over the years, and after thousands of calls, IMI has collected a series of tips and best practices. These not-so-secret paths to success may often seem simple, but they cause the large majority of problems in masonry buildings.

This article is not meant to be an exhaustive discussion on any single item, but rather an overview of the most common questions, problems, and barriers to a high-performing masonry structure.

The most common lessons learned fall into these categories:

- ‘systems’ thinking;

- understanding material properties;

- system interfaces;

- moisture, air, and vapour control;

- cost control;

- movement control;

- stains and cleaning;

- communication; and

- workmanship.

Photo © Serenia Holland. Photo courtesy IMI

Photo © Tom Nagy

‘Systems’ thinking

Since a change in a single component of the entire building enclosure system can affect the whole system’s performance, any alteration in material or detailing should be evaluated in light of how it alters the greater whole. For example, a seemingly simple change of a weep vent for cost reasons may profoundly impact the wall’s function and esthetics. The road to poor performance is often paved with good intentions.

There is the erroneous belief if a little insulation is good, then a lot of it must be better. Leaving aside the argument of diminishing marginal return on increased cost, a side effect of additional insulation is potentially shifting the dewpoint, minimizing air space, or requiring a different veneer tie system.

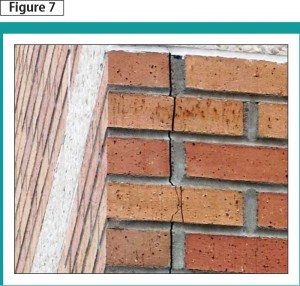

Changing the veneer material due to esthetics, cost, or other reasons can also pose problems. On a recent project, the architect decided to replace the clay brick veneer units with concrete masonry units (CMUs). While both options are acceptable choices and perform well at a fair price, concrete blocks have different characteristics than clay masonry, and the movement control strategy must also change. Clay masonry expands with both thermal and moisture expansion; CMUs, on the other hand, tend to shrink due to losing moisture. When the original details for movement control were left unchanged, the veneer experienced cracking.

Photo © Dave Collins

Photos © Pat Conway

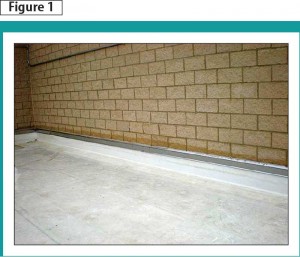

Where two trades meet, one should take special care both parties understand the details for how they connect or relate. Since an enclosure is a single working system, one should think about using a single source for the installation. A good example is the low-roof/tall-wall detail. In Figure 1, the mason and roofer both installed their products, but water was trapped below the level of the drainage vent or weep. IMI recommends a site meeting with all parties before installation of this critical detail.

A wall section includes installation of the control layers of moisture, air, and vapour barriers, thermal insulation, and the masonry ties. If a single trade installs all these items, one minimizes scaffolding needs and the scheduling issues with trade co-ordination. Also, one trade is responsible for patching or repair of the control layers during the construction phase. IMI trains members of the International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers (BAC) in all these building enclosure items (Figure 2).

Material properties

It is critical to take the time to read the appropriate standards for the materials chosen and specified. An issue that repeatedly comes up is the dimensional tolerance for brick. According to Canadian Standards Association (CSA) A82-06, Fired Masonry Brick Made from Clay or Shale, Table 3, the maximum permissible variation from specified dimension is 8 mm (0.3 in.) for a brick specified between 200 and 300 mm (7.9 and 11.8 in.).

There are further requirements for the average brick in the job lot sample, but the point is to remember brick, or clay masonry, has a material tolerance. When examining a wall, it is important to remember while a bricklayer tries to keep head joints in alignment, there may be some acceptable variance due to material properties.

If a designer references a standard in job specifications, the material must demonstrate its compliance. One should ensure he or she knows the requirements of such standards.

Watch the interfaces

A vice-president of field operations for a major construction manager recently had some valuable input for the building envelope.

“The biggest place a subcontractor can help the performance is to watch the gaps,” he told this author. “When two trades have work that meets, who is responsible for the gap? If a window meets a brick wall, and each trade has a given tolerance, I need assurance the size of the sealant joint is going to meet design. I don’t need finger-pointing and a fight between trades.”

This common complaint applies to material tolerances, trade jurisdiction, and, most importantly, good communication between all parties.

It is IMI’s contention brick does not leak. However, water enters a masonry wall system through the interface of masonry and a dissimilar material. Mortar joints, cracks, window jambs, sills, and heads are all potential sources of problems where one material interfaces with another, and all take special attention from the parties involved. One should watch the interface.

Control the moisture

Moisture penetration is the enemy of a good building enclosure. From a craft standpoint, the first line of defence against water penetration with unit masonry is good workmanship. Full head and bed joints are critical––particularly the vertical head joint since it does not have the wall’s dead load to help compress the mortar for a more dense mortar joint (Figure 3).

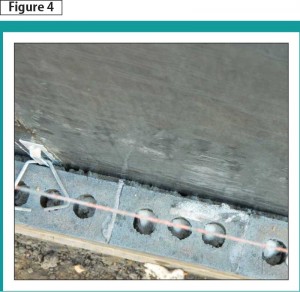

In cavity wall construction, one should ensure the air space is wide enough. IMI recommends a 51-mm (2-in.) clear space for ventilation and drainage. Smaller air spaces can lead to mortar bridging and tapered air spaces in the case of support walls being slightly out of tolerance (Figure 4).

One should ensure flashing extends past the face of the wall. It is best practice from a functional and esthetic perspective to have the flashing extend out of the wall with a metal drip edge. It is also important to ensure flashing is properly installed to prevent oozing of heat-unstable membranes.

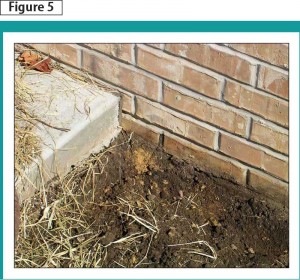

Inserting below-grade weeps allows drainage above grade––another example of trade co-ordination (Figure 5). This author knows of a project where the landscaper put the grade higher than the weeps. A similar problem occurs when a maintenance person, in good faith, decides to put a sealant joint over all of those weeps, thinking they are simply voids a bricklayer forgot to fill with mortar.

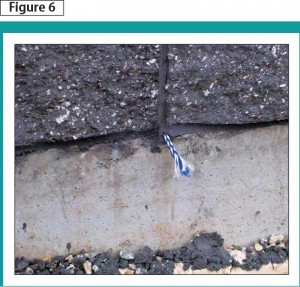

One should also check all applicable codes and standards, and ensure specifications are carried out in the field. Figure 6 shows a nylon rope wick in place of the specified open vent.