Introducing energy recovery ventilation

By Steve Ulm

Current Canadian projects indicate energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) are not a fad, but the wave of the future. One project putting this type of HVAC technology on the ‘sustainability map’ is the Montréal-based Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM). CHUM’s 185,810-m2 (2-million-sf) expansion (pictured above) makes it one of the largest hospitals in North America. Its 47 ERVs will provide 100 per cent outdoor air for optimal indoor air quality (IAQ).

While most hospitals bring in 50 per cent or less of outdoor air, CHUM’s total 2.8 million-cfm design of 100 per cent outdoor air will enhance IAQ and minimize the escalating global trend of hospital acquired infections (HAI). The ERVs will also significantly reduce the energy costs of conditioning outdoor air.

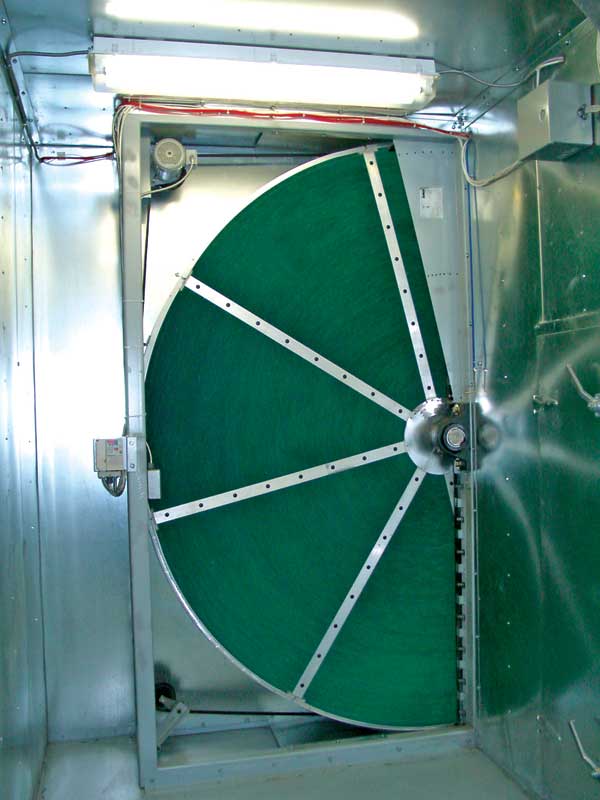

ERVs work in a variety of ways, but one of the most popular methods for Canada’s diverse climate includes desiccant-based units. Enthalpy wheels outfitted with desiccant materials absorb moisture out of humid outdoor air. This lessens the humidity load conventional air-conditioning systems handle, which results in significant energy savings.

Besides humidity control, heat recovery is another advantage. ERVs can use exhaust air to preheat or pre-cool outdoor air before it is conditioned to a set point, such as 22 C (72 F). For example, heating —––23-C (–10-F) Canadian outdoor air in January to 22 C is a significant expense. However, using 18-C (65-F) exhaust air to preheat the outdoor air will deliver

significant savings.

Aside from the estimated millions of dollars in energy savings over the operational life of CHUM, the healthcare facility’s ERV system will help achieve a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Silver certification. The downsizing of mechanical equipment due to the energy recovery strategy and other sustainable efforts is expected to displace 40,000 tons of carbon emissions annually. Further, an estimated 55 million L (14.5 million gal) of cooling-tower water will be saved yearly due to cooling system reductions.

Canada’s upward trend in ERV use is also partially due to local code jurisdictions, which are continually adopting more elements of the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) standards. For example, ERVs offer energy-saving advantages to help buildings comply with ASHRAE 90.1, Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-rise Residential Buildings. They also offer IAQ advantages for complying with ASHRAE 62.1, Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality, and ASHRAE 55, Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy.

Using, promoting, and teaching ERV

Perhaps the poster child of Canadian ERV is Sheridan College—an Oakville, Ont., post-secondary school that may soon be considered one of the nation’s most sustainable higher education buildings.

Sheridan’s 12,077-m2 (130,000-sf) Skilled Trades Centre uses a 23,000-cfm dedicated outdoor air system (DOAS) ERV with molecular sieve desiccant enthalpy wheels to supply about 48,310-m2 (520,000-sf) of workshop and lab spaces. A second 19,000-cfm ERV uses hybrid system to supply active chilled beams in 20 classrooms.

The state-of-the-art building, which also uses light-emitting diodes (LEDs), rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems, daylight harvesting, rainwater systems, and other sustainable technologies, will not be certified to LEED, even though its accumulated credits can qualify for Silver. While other universities target LEED ratings for new buildings to achieve annual energy intensities of 160 to 170 kWh/m2, the two ERVs are expected to help the Skilled Trades Centre reach a Sheridan-mandated energy intensity limit of 100kWh/m2 according to the school’s sustainable energy systems manager, Herbert Sinnock, CET/CEM, CMVP, LEED AP and project manager, Katherine Rinas.

The Skilled Trades Centre is part of a 30-year climate and energy master plan Sheridan created in 2012. The plan expects to reduce carbon emissions by 50 per cent and energy consumption costs by several million dollars by 2020. ERVs in the facility, as well as previous Sheridan projects, play an important role in the plan.

Another indication ERVs are here to stay in Canada is Sheridan’s plan of publicly promoting its two ventilators to cultivate public interest in the technology. Both ERV units are installed in a third-level mechanical room, fully visible from corridor passersby via a wall of glazing. A corridor-mounted LED dashboard from the building automation system (BAS) reflects real-time ERV statistical data and equipment operating diagrams.