Function Meets Esthetics: Using architectural concrete formliners

By Ray Clark and Bob Fedchyshyn

There has always been a quest to incorporate esthetically pleasing elements into building façades. The most prolific examples are found in early Greek and Roman architecture. Affluence in these two societies was deeply rooted and expressed through lavish building exteriors. These designs were so impressive many elements of modern-day architecture can be traced to those eras.

The ornate columns and hand-cut stone building blocks make a bold statement through esthetics, but also provided function. So much ‘function’ in fact, the grandest of these structures are more than two millennia old. The early designers and constructors of these ancient buildings were setting the stage for a ‘drab-to-fab’ revolution in building exterior architectural finishes.

Early building design and materials were relegated to what was readily available from the earth. Egyptians used straw, mud, gypsum, and lime to form bricks and mortar in the construction of the pyramids. The Romans used a material similar to modern cement and combined it with animal products that acted as admixtures. However, it was not until 1824 when England’s Joseph Aspdin came up with portland cement.

As the main ingredient in concrete, this material catapulted the design and construction industry forward. The century following Aspdin’s invention saw many historic firsts within concrete construction, from the first reinforced bridge in 1889 (San Francisco) to the first skyscraper in 1903 (the Ingalls Building in Cincinnati). Concrete and concrete masonry units (CMUs) soon became the construction material of choice for many designers throughout the world.

With this advancement, came the increased desire for patterns, textures, and colours. Coloured concrete was introduced in 1915 when Lynn Mason Scofield begain producing colour additives for concrete; a half-century later, manufactured patterns became possible. With the advent of formliners, patterned concrete once only achievable through handcrafting could now be replicated in a controlled and more expedient fashion while maintaining the classic look borrowed from ancient architecture. In the 1970s, formliner manufacturers were able to add textures.

Types of formliners

Contemporary formliners lend an almost endless array of pattern and texture opportunities. North American manufacturers provide a standard selection of products, with some offering more than 300 choices.

In the 1970s and 80s, ribbed patterns were widely used in designs for sound walls, industrial buildings, mass transit stations, and other various building exteriors. As polyurethane formliners emerged, the ribbed patterns gave way to more natural and unique patterns. This provided the architect with more options and flexibility when designing a concrete building exterior.

Patterns and textures previously only available by extracting them from natural materials are now exactly replicated in formliners. Even the most traditional building materials, brick and block, have been recreated. Stone, wood, stucco, masonry, and abstract esthetics can all be incorporated in designs.

The products themselves are available in several different materials—styrene plastic, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic, and polyurethane rubber. Each of these materials has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Styrene

Styrene plastic formliners are inexpensive ($16 to $32 per 1 m2) and lightweight, for example, but are unable to achieve the deep relief and texture associated with polyurethane formliners. Additionally, most styrene plastic formliners are suitable for a single use—they must be discarded after concrete is poured and removed from them.

ABS

ABS plastic formliners, in the mid-range of pricing ($37 to $86 per 1 m2), are not as heavy as polyurethane formliners, and provide moderate relief and texture. These products are suitable for 10 to 15 uses.

Polyurethane

Polyurethane formliners are the most expensive of the three products ($96 to $800 per 1 m2), but provide the best relief and texture. Further, they can be used more than 100 times. Therefore, they present the best value for medium- to larger-sized projects that require more pattern and texture definition. In fact, lifecycle costs for polyurethane formliners can be as low as pennies per square metre.

formliner.

Customizable options and manufacturing

Most formliner manufacturers have the ability to produce custom-made materials, broadening the realms even further for building design. Formliners are originally created from a master mould, which can be developed from elements found in nature, crafted by an artisan, or through utilization of computer numerical control (CNC) milling machinery.

On completion of the master mould for the custom formliner, the design professional will either approve the design or suggest modifications. Once accepted, the master mould will ultimately be used to cast formliners a precast manufacturer or contractor will employ to produce the architectural concrete element. Depending on the agreement between the formliner manufacturer and the project designer or owner, the custom mould may be retired or become the property of the project owner. This may further enhance uniqueness, especially if the custom formliner is reserved for that particular project.

New technology allows the design professional to think even further outside the box. Photoengraved and 3-D relief formliners provide life-like images never before possible in concrete or masonry design.

Photoengraved

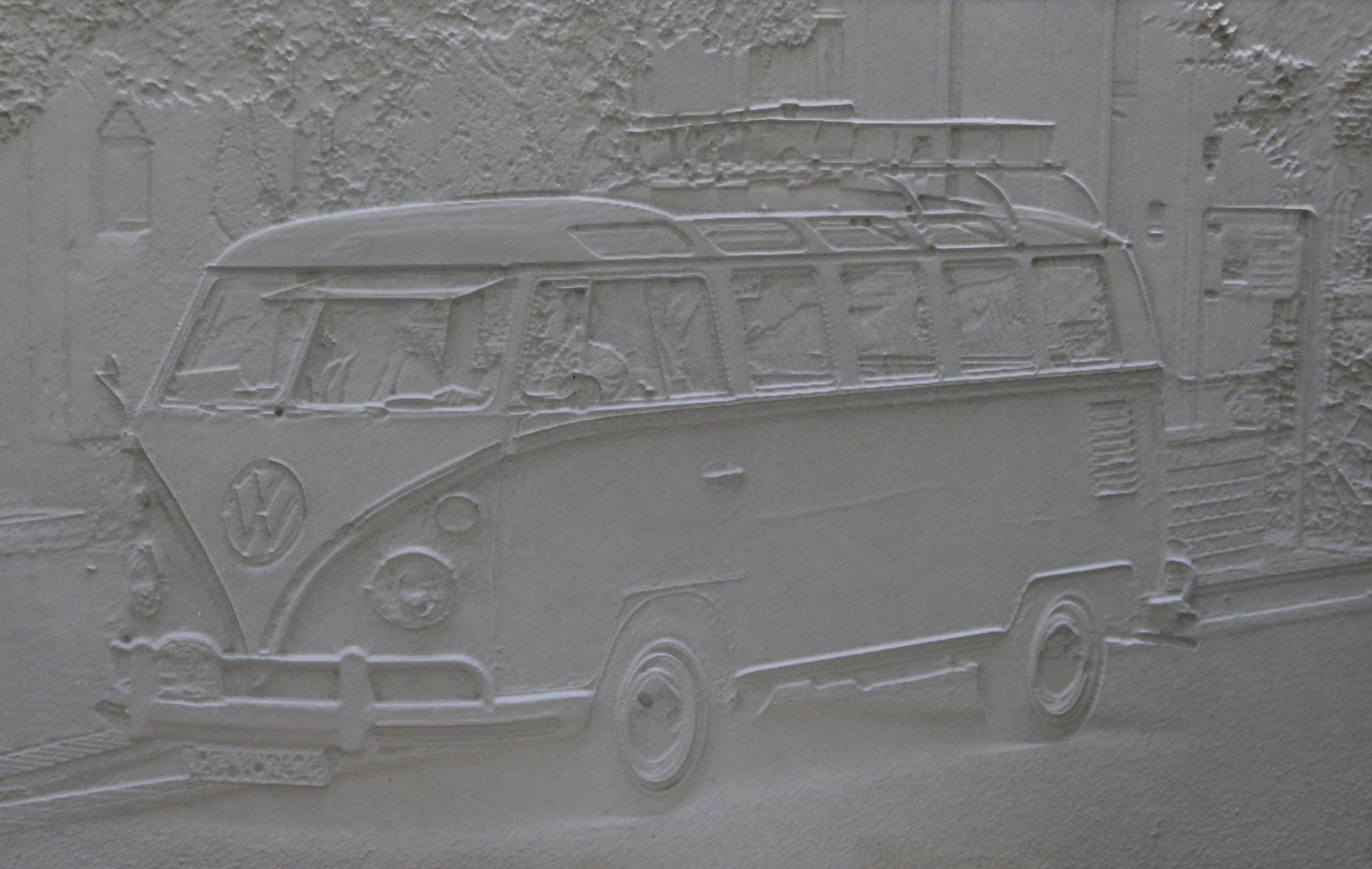

Photoengraved formliners come about as the result of an unusual design process achieved through a transfer of actual images onto a panel using a computer-guided milling technique. The photograph is scanned and converted into a 256-colour greyscale image and then developed into an electronic file read by a special CNC milling machine.

The CNC machine creates a master mould used to create the formliner onto which concrete is poured. The resulting element produces an exact image of the original photograph. The concrete panel comes to life through the play of light and shadows on the façade; the photographs are more apparent when light is projected from the side. The sun’s movement throughout the day gives rise to changing image effects on the building. Exterior and interior applications of photoengraved concrete can be accentuated by the use of artificial light sources. Photoengraved liners have been used throughout the world on sports arenas, museums, and educational institutions.

Three-dimensional concrete

Unlike photoengraved concrete, 3-D concrete does not rely on light and shadowing to project the image. Rather, an image is represented through geometrical contours. The development process is similar to the photoengraved technique in that it transfers an exact image of a photograph to a CNC milling machine.

Software is used to convert the photograph into a three-dimensional milling file. It is then transferred to a plate material on the CNC machine, thereby creating a master mould that is then used to create a formliner. The 3-D formliners can be created in any size; they are only limited by the maximum dimensions of the plate material and the maximum milling area of the CNC machine. Applications are virtually unlimited because almost any image in standard graphic formats can be used. While 3-D concrete has been used in outdoor projects, it is especially suited for indoor applications where it can be more readily viewed in closer detail.

Like all other exterior products used on building façades, concrete with 3-D images or photoengraving can be subjected to damage. However, concrete is a durable and long-lasting product. Should damage occur to one of these elements, it may be repaired onsite if it is isolated. When major damage occurs, it will need to be replaced.

Adding colour

Historically, precast concrete elements employing formliners have been produced without colour. However, precast manufacturers or concrete contractors introduced pigments into the mix to provide integral colour—though this also made for a more-expensive product.

A new method was developed 25 years ago that allowed concrete elements to be stained after production. Concrete stain, unlike paint, penetrates the concrete surface and forms a chemical bond, resulting in a more durable surface. Additionally, while paint tends to mask a surface texture, stains allow the prominent features to be retained. Integral colouring of concrete used in traditional manufacturing introduces a host of potential challenges including colour bleeding or differences from the intended colour target. Staining alleviates these problems and allows a more cohesive, homogenous look to the finished product.

Recent examples of precast concrete elements incorporating formliners and colour staining can be found in a plethora of projects in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Designers have discovered the value of using precast concrete, formliners, and colour to achieve stunning results.

Precast concrete panels that closely replicate brick masonry finishes and colours are now widely used in high-rise buildings. Even to the trained eye, it is extremely difficult to distinguish the difference between a brick-textured, coloured precast panel from an authentic brick wall. Precast concrete significantly reduces construction costs through speed of installation and labour savings.

Panels treated with formliners and stain can be erected in a more expeditious manner than traditional masonry construction. Typically, building with masonry is susceptible to weather conditions, whereas precast concrete panels can be installed without much concern to weather. In this author’s experience, project owners can benefit from a savings of 10 to 30 per cent with precast concrete construction versus traditional masonry construction.

Other considerations

All formliners have seams at some point in the pattern, depending on the size of the liner used and subsequent precast panel poured. If a designer wants limited seams in the finished product, a larger-sized formliner must be used so seams do not appear as often. Alternatively, the designer may want to work with the seams and accent them as part of the design.

Limitations of formliners may include the life expectancy of each type of material. As mentioned, most plastic and polystyrene products have single or limited usage. Polyurethane formliners, however, can be employed more than 100 times. Another challenge can involve sizing—all will have maximum sizes in terms of their dimension. (Most formliners can be made in sizes less than their dimensions.)

Using formliners instead of traditional carving has no impact on durability since the products are merely casting a pattern and texture directly onto typical concrete. In comparison to traditional masonry or concrete, the only occasion in which moisture management becomes an issue is when the pattern and/or texture is so deep it could accumulate liquid water or ice, causing damage during freeze-thaw cycles. Accordingly, a designer should consider this when selecting a pattern and texture.

Conclusion

For architects and project owners, precast concrete construction provides an unrivaled value through function and esthetics. What was once thought as an impossible feat in the concrete industry has now been realized through the advancement and combination of formliners and concrete staining.

Plain, colourless, and un-textured precast concrete panels are a thing of the past. Design professionals have discovered designing with attractive and functional vertical concrete surfaces expands the realm of possibilities and introduces an entirely new world of architectural wonder.

Ray Clark has been actively involved in the concrete products industry for 15 years, now serving as general manager of US Formliner. He is the company’s representative at the Canadian Precast Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI). Clark has been an instructor for various Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute (ICPI) permeable interlocking concrete pavement (PICP) courses. He can be reached at ray.clark@usformliner.com.

Ray Clark has been actively involved in the concrete products industry for 15 years, now serving as general manager of US Formliner. He is the company’s representative at the Canadian Precast Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI). Clark has been an instructor for various Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute (ICPI) permeable interlocking concrete pavement (PICP) courses. He can be reached at ray.clark@usformliner.com.

Bob Fedchyshyn is the general manager of Canadian operations for Toronto-based Nawkaw. He has more than 20 years of experience, assisting design/construction professionals throughout North America. Fedchyshyn is a member of the Toronto Construction Association (TCA), Canadian Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI), and CSC. He can be contacted via e-mail at bfedchyshyn@nawkaw.com.

Bob Fedchyshyn is the general manager of Canadian operations for Toronto-based Nawkaw. He has more than 20 years of experience, assisting design/construction professionals throughout North America. Fedchyshyn is a member of the Toronto Construction Association (TCA), Canadian Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI), and CSC. He can be contacted via e-mail at bfedchyshyn@nawkaw.com.