Balcony Glazing: What has happened and where we are now

By Greg Hildebrand, M.Sc. (Eng)., CET

In the summer of 2011, there were numerous incidents of spontaneous breakage of monolithic tempered safety glass employed in balcony guard infill panels or balustrades. As some of these occurrences were located in Toronto, the subject of balcony guard glass became a media obsession. For balcony guard designers, manufacturers, glass processors, building developers, building officials, and condominium owners, the subject became a nightmare.

Initially, armed with few facts regarding the nature and extent of the problem, developers of properties apparently afflicted with spontaneous glass breakage issues (or failure of the entire guard assembly) reacted by requesting access to glass-clad balconies be restricted to protect unit occupants. To potentially protect the public, the remaining glass was either secured with safety netting for the short term or, in some cases, the original monolithic tempered glass was completely replaced with heat-strengthened laminated glass that would theoretically remain in place in the event of breakage. This action, however, raised the question of a specific guardrail design’s ability to retain the broken laminated glass until replacement.

These actions were costly, with the industry shouldering millions of dollars in temporary measures and remediation costs. What was more troubling was the lack of a definitive path forward, as the engineering community was only beginning to understand the nature and magnitude of the problem. This factor had a further effect on the building industry as production was paralyzed, while regulators mandated developers provide them with proper engineering rationale to ensure materials would serve their intended purpose. As it happened, this turned out to be a problem.

Further issues

Considering the obvious material issues associated with the failed glass (i.e. nickel sulfide induced spontaneous breakage of the tempered glass), the engineering community subsequently determined there was no substantive guidance regarding the design and use of balcony guardrail systems, other than the information given in the national and provincial building codes. In other words, there is no applicable reference standard for these crucial safety components.

Other issues included the fact designers follow different protocols in the design of guardrail systems—some consider the guard loads independently, others consider guard and wind loads separately, and some a combination of both. Clarification with code officials indicates the combination load approach is the appropriate method to employ.

For wind, two different methods are employed to establish load. The first involves the calculation of the wind load according to the procedure given in Part 4 of the Ontario Building Code (OBC) and results in overly conservative loads while the wind tunnel study results are varied (but still conservative). The second method involves obtaining estimates by testing scaled building models in a wind tunnel study.

Additionally, there is no guidance in existing codes and standards regarding tempered and laminated safety glass in balcony guardrail systems (or these assemblies’ design).

Other notable findings included:

- data relating to actual wind loads acting on guardrail assemblies was unavailable;

- numerous lucid arguments from other jurisdictions supporting the practice of employing guard and wind loads independently (i.e. the odds of two rare events—such as peak wind and maximum outward guard load—occurring at the same time is statistically insignificant, even if either load is factored down);

- mandated guidance regarding post-breakage retention for glass infill or balustrades was unavailable; and

- there are no mandated test procedures to evaluate a balcony guard system for guard load, wind load, and impact testing.

Based on initial findings, it became clear there was a need to develop a Canadian standard for guardrails in buildings. However, this can be a lengthy progress, so a temporary measure was required in the interim.

Temporary remedy

To this end, the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (MMAH) established an advisory panel to conduct a review and provide advice to OBC standards for glass panels in balcony guards.

This report states:

The Panel’s mandate was to make recommendations on whether and how the Building Code may be amended to address the problem of the breakage of balcony glass and its risk to persons nearby. It was not the mandate of the Panel to make findings of fault or assign blame.1

This committee—chaired by MMAH building and development staff—consisted of approximately 25 stakeholders including engineering and building code consultants, developers, contractors, professional designers, municipal building departments, the insurance sector, National Building Code of Canada (NBC), and Canadian Standards Association (CSA).

After several meetings, the expert committee developed seven recommendations for consideration:

1. That the [Ontario] Building Code [OBC] be amended to provide supplementary prescriptive requirements for all glazing in interior and exterior guards in all buildings, except houses (this excludes detached houses, semi-detached houses, duplexes, triplexes, townhouses, and row houses).

2. That consideration be given to clarifying that direct glass contact with any metal or similar hard elements is to be avoided and to require sufficient allowances for deflection and movement under loads and temperature changes. This clarification could be included as a note in the Appendix to the Building Code.

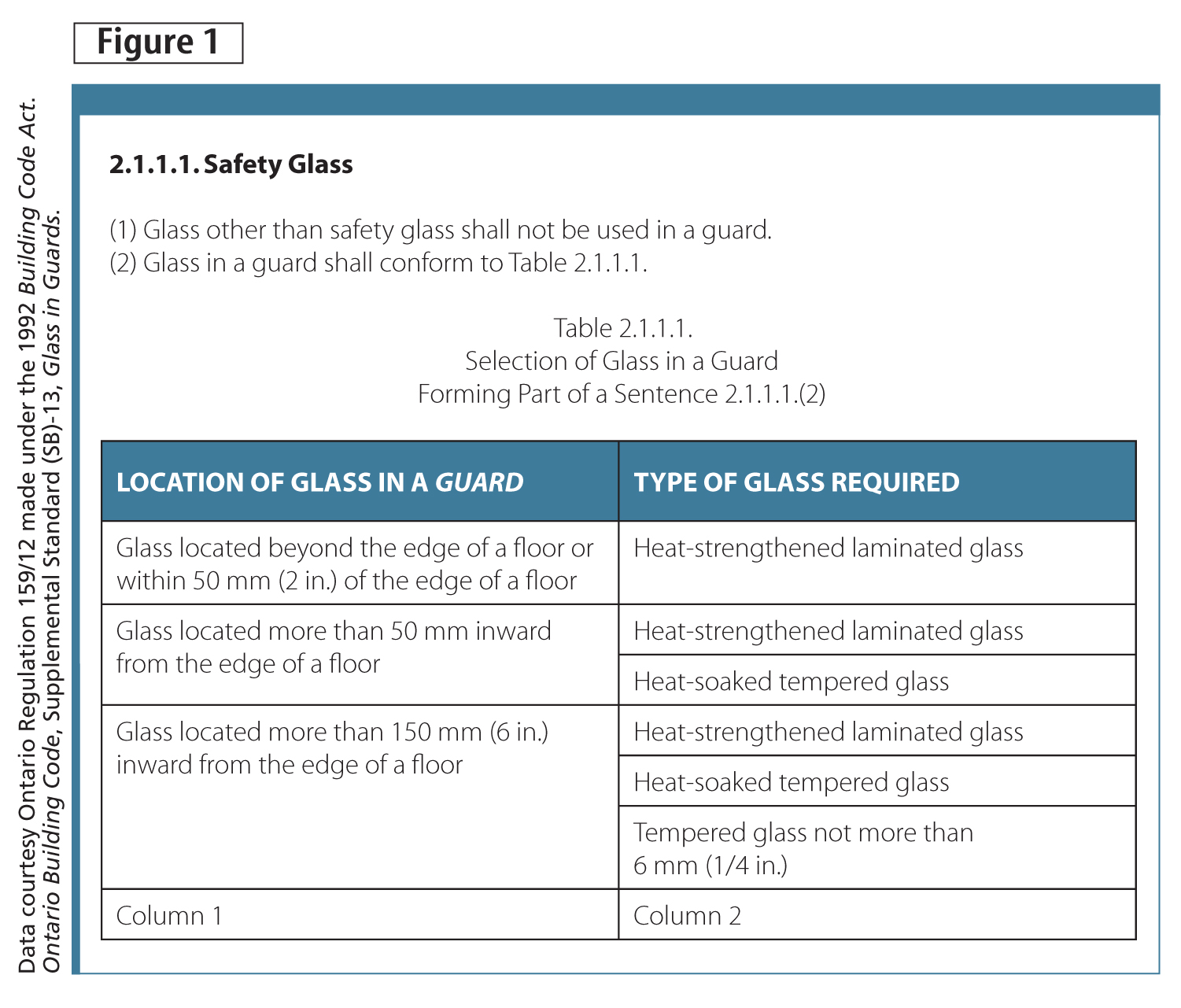

3. Where it is incorporated in a guard, glazing located beyond the edge of a floor, or within 50 mm [2 in.] of the edge of a floor, shall be heat-strengthened laminated glass that is designed, fabricated, and erected so that, at the time of failure of the glass, the glazing does not dislodge from the support framing.

4. Where it is incorporated in a guard, glazing located more than 50 mm to 150 mm [6 in.] inward from the edge of a floor shall be fully heat-soaked tempered glass or heat-strengthened laminated glass that is designed, fabricated, and erected so that, at the time of failure of the glass, the laminated glazing does not dislodge from the support framing.

5. Where it is incorporated in a guard, glazing located more than 150 mm inward from the edge of a floor shall be heat-strengthen laminated glass or heat-soaked tempered glass. However, tempered glass is permitted where the glazing does not exceed 6 mm [0.23 in.] in thickness. Guards using heat-strengthen laminated glass must be designed, fabricated, and erected so that, in the event of failure of the glass, the glass does not dislodge from the support framing.

6. That the memorandum, dated March 8, 2012, from Cathy Taraschuk, P. Eng., reporting on the advice of the Task Group on Live Loads Due to Use and Occupancy of the Standing Committee on Structural Design on the applicability of the load combinations listed in Table 4.1.3.2.A. of Division B of the 2010 Model National Building Code be included as an Appendix to the Building Code.

7. That the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing:

(a) support the development of the proposed CSA Group Standard on Balcony Guard Rails; and

(b) will consider referencing the CSA Group Standard on Balcony Guard Rails, once it is published, in the Building Code. 2

Despite the fact these seven recommendations did not receive unanimous support within the expert panel, their prescriptive elements were incorporated into the 2006 Ontario Building Code in the form of Supplemental Standard SB-13, Glass in Guards, which came into effect July 2012 (Figure 1).

In addition to setting out the glass type requirements, it also references European Deutsche Industrie Norm (DIN) Standard EN 14179-1, Heat Soaked Thermally Toughened Soda Lime Silicate Safety Glass, for a heat soak process to be carried out for monolithic tempered glass to reduce residual risk of spontaneous breakage due to nickel sulphide inclusions. Before this reference, there was no mandated heat soak requirement in North America, in spite of the fact spontaneous glass breakage is well-known in the industry and the procedure is often carried out by some manufacturers for safety glass used for this type of application.

The amendments came into effect July 1, 2012 and only apply to new construction and major renovations. The building code does not generally require retrofitting of existing buildings, although for recently constructed high-rise building owners in Toronto, a directive to have balcony guard assemblies assessed to ensure they meet SB-13, Glass in Guards, was announced.

Standard development

Concurrent to the work being carried out by MMHA’s expert panel, CSA was working with the engineering community to initiate the development of a new standard to cover all aspects of building guards, including the subject of glass in guards.

The first task in the standard’s development was to establish a budget and solicit funding from various stakeholders. An initial outline was presented to potential contributors in November 2011. In addition to background information, the preliminary outline of the standard’s potential content included:

- an introduction discussing applicability, specification guidance, and performance parameters;

- general scope including terminology unique to the subject;

- relevant referenced publications such as British Standards Institute (BSI) or ASTM standards for materials and testing;

- definitions for loads (guards and wind), assembly types, and applications;

- general requirements for specific applications and assembly types, including loading requirements;

- test requirements including sequence, test specimen sizes, details, and testing methodologies;

- material requirements setting out prescriptive requirements for the balcony guardrail system components; and

- requirements outlining how specific guard load components are to be used in-situ.

On receiving sufficient preliminary financial support, potential technical committee members were identified and the inaugural meeting of the new CSA A500, Building Guards, technical committee was held in June 2012. A final technical committee of 32 voting and nine non-voting (i.e. associate) members were confirmed. The technical committee’s mandate was also established.

The standard specifies requirements for permanent guards in and around buildings. It does not apply to temporary guards, barriers for resisting impact from vehicles, or barriers used in building operations and works of engineering construction.

Conclusion

Currently, the technical committee consists of a number of task groups mandated to specifically develop technical content for the standard. These task group categories and topics include:

- materials, components, and methods of design and construction(i.e. fastening anchorage and connections, materials, review, and comparison of relevant codes and standards);

- preliminary considerations(i.e. categories and locations of guards, durability and lifecycle of assembly, and safety and risk assessment);

- design criteria (i.e. loads and their combinations, design parameters—including loads, vibration, deflection, post-breakage—and guard layout);

- testing procedures;

- assembly installation requirements; and

- inspection(construction and post-construction review).

Additionally, the standard will include informative sections addressing such items as guard repair and maintenance.

The CSA A500 standard technical committee has tentatively established a conservative schedule of 24 months to complete the standard. At this stage, the committee is moving forward at a reasonable speed; accordingly, a 2014 publication date should be anticipated.

Notes

1 For more information, see Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing’s (MMAH’s), “Report of the expert panel on glass panels in balcony guards,” March 30, 2012, Toronto Ontario. (back to top)

2 This was originally published in Pushing the Envelope, a publication of the Ontario Building Envelope Council, Spring 2013. (back to top)

Greg Hildebrand has been employed in the building science lab and field testing and consulting field for more than 30 years. Currently, he is the head of the façade engineering group of the building engineering team at exp Services Inc. In addition to being a member of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) A500, Guard Standard, Hildebrand is the Canadian chair of the North American Fenestration Standard Joint Document Management Group and vice-chair of the CSA A440 Window Standard Technical Committee. He can be contacted via e-mail at greg.hildebrand@exp.com.

Greg Hildebrand has been employed in the building science lab and field testing and consulting field for more than 30 years. Currently, he is the head of the façade engineering group of the building engineering team at exp Services Inc. In addition to being a member of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) A500, Guard Standard, Hildebrand is the Canadian chair of the North American Fenestration Standard Joint Document Management Group and vice-chair of the CSA A440 Window Standard Technical Committee. He can be contacted via e-mail at greg.hildebrand@exp.com.